‘An embarrassment of riches’: ‘The Gay Harlem Renaissance’ opens at The New York Historical

On Oct. 9, the New York Historical (which last year dropped “Society” from its title) hosted a spectacular evening to fête the opening of its much-anticipated exhibition, “The Gay Harlem Renaissance.” Scholars spoke of history, sponsors of community, a vocalist sang blues ballads to four-piece accompaniment, dancers performed the Charleston and the Lindy Hop in … Read More

On Oct. 9, the New York Historical (which last year dropped “Society” from its title) hosted a spectacular evening to fête the opening of its much-anticipated exhibition, “The Gay Harlem Renaissance.”

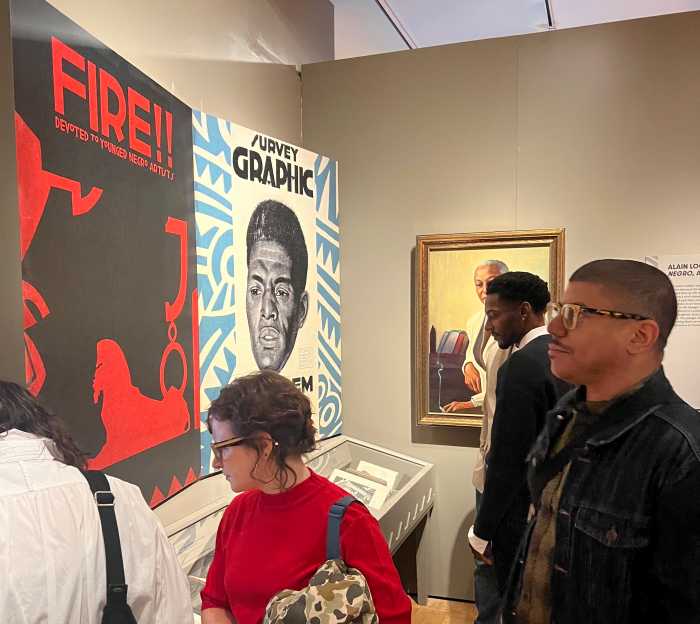

Scholars spoke of history, sponsors of community, a vocalist sang blues ballads to four-piece accompaniment, dancers performed the Charleston and the Lindy Hop in a recreated Prohibition-era nightclub, and guests immersed themselves in this multimedia exhibition charting, literally and figuratively, the omnipresence of LGBTQ individuals and sensibilities in Harlem of the 1920s and ‘30s, a period of cultural outpouring from African American and Afro-Caribbean creators at all echelons of society given the moniker, “Harlem Renaissance.”

[caption id="attachment_59720" align="aligncenter" width="525"] The entrance to the exhibition at the New York Historical. Unidentified photographer, Gladys Bentley, 1946-1949.Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture[/caption]

The entrance to the exhibition at the New York Historical. Unidentified photographer, Gladys Bentley, 1946-1949.Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture[/caption]

“The idea first emerged when George Chauncey, who is a professor of history at Columbia University, joined our board of trustees and presented the concept of doing a show celebrating that many of the contributors to the Harlem Renaissance were LGBTQ+, on the centennial of Alain Locke’s ‘The New Negro,’” said lead curator Allison Robinson, referring to the hefty anthology published in 1925, edited by Locke, distinguished academic, who, like a number of the volume’s writers, was gay.

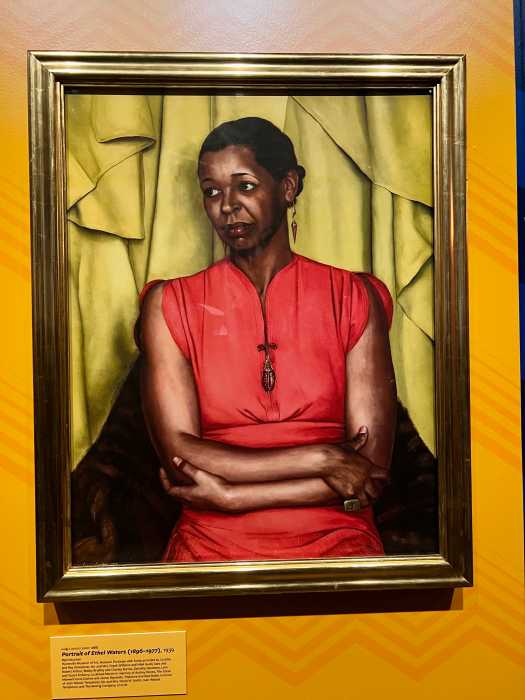

The show features a portrait of Locke, and ones of other figures prominent in either high society or popular culture. A standout is the evocative painting of jazz and blues singer and Broadway actress Ethel Waters, rendered at the height of her fame by Italian-born artist Luigi Lucioni (whose other subjects at the time were handsome male acquaintances of his down in Greenwich Village).

[caption id="attachment_59717" align="aligncenter" width="525"] Portrait of Ethel Waters by Luigi Lucioni, 1939.Huntsville Museum of Art[/caption]

Portrait of Ethel Waters by Luigi Lucioni, 1939.Huntsville Museum of Art[/caption]

“Harlem was the most gay-friendly neighborhood in New York,” said Chauncey, whose seminal book, “Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940,” was published to high acclaim in 1994. “Its queer scene was far larger, livelier, and bolder than the better-remembered white gay scene in Greenwich Village. And, Black society was more accepting than white.”

One highlight of the exhibition is an interactive modification of a 1933 map by pathbreaking illustrator E. Simms Campbell showing the multiple entertainment venues that dotted Harlem, many of which included queer entertainers or patrons.

The exhibition revisits elite circles and working-class settings alike, and both public and private lives, carrying visitors from renowned literary salons and nightclubs to unsung speakeasies and rent parties. Even wardrobe closets. Alongside Waters’ portrait, for example, is a pair of her rhinestoned pumps, sheet music from her performances at the legendary Cotton Club, and ephemera referencing her girlfriend, the dancer Ethel Williams.

“We’ve represented painting, sculpture, drag performance, music, literature, all in this gallery,” Robinson said. “If anything, it was an embarrassment of riches” to curate.

[caption id="attachment_59718" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Visitors at the opening of the “The Gay Harlem Renaissance" exhibition.Nicholas Boston[/caption]

“The Gay Harlem Renaissance” comes at an embattled time for museum curatorship nationwide, with the cancellation of similarly-themed exhibitions.

“We believe, in everything that we do, that remembering completely and truthfully is an act of justice,” said Elizabeth Alexander, president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, lead sponsor of the show. “Art, when we get to see the whole story, helps us see ourselves and each other.”

Visitors at the opening of the “The Gay Harlem Renaissance" exhibition.Nicholas Boston[/caption]

“The Gay Harlem Renaissance” comes at an embattled time for museum curatorship nationwide, with the cancellation of similarly-themed exhibitions.

“We believe, in everything that we do, that remembering completely and truthfully is an act of justice,” said Elizabeth Alexander, president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, lead sponsor of the show. “Art, when we get to see the whole story, helps us see ourselves and each other.”

The picture “The Gay Harlem Renaissance” paints is not all rosy. Gay and lesbian Harlemites had their own brushes with policing, moral and actual, from within and outside. For the intellectuals and community leaders, the burden of respectability was heavy. Most of the men were out only as far as open secrets, several marrying socialite brides as “beards.”

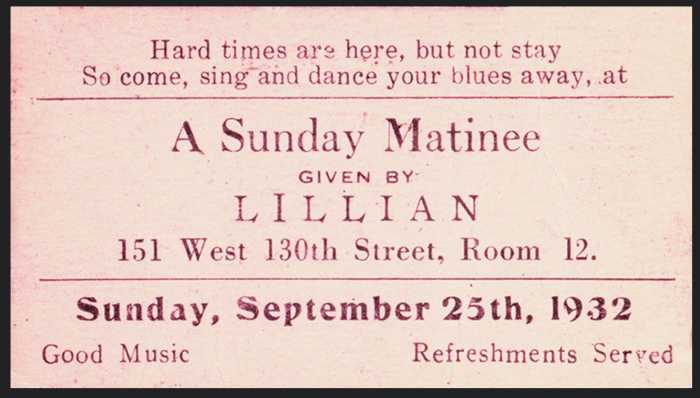

Then, there was surveillance by law enforcement. In separate sting operations, the writer Wallace Thurman and Augustus Granville Dill, business manager of the NAACP’s magazine, “The Crisis,” were arrested for “homosexual activity” in public men’s rooms. Mabel Hampton, the dancer turned activist, was wrongfully brought up on charges of prostitution for which she served time in a reformatory. Hampton’s fortune would later change with a chance meeting at a bus stop with Lillian Foster, who handed her a calling-card sized invitation to her rent party, commonly held in those days.

“Mabel went,” Chauncey said. “They ended up living together for more than 40 years and Mabel kept this card for the rest of her life.” The card is on display, as is a typed letter Thurman sent to a friend disclosing details of his arrest and the hoops he jumped through to not only extricate himself but keep the incident hush-hush.

[caption id="attachment_59721" align="aligncenter" width="700"] Unidentified maker, Rent party ticket, 1932.From the Mabel Hampton Collection, Lesbian Herstory Archives[/caption]

“We’re less interested in identifying which artists were queer,” Chauncey said, “than in showing how queer mentorship, creativity and the gay-centric friendship circles forged by these artists advanced the cultural flowering of this era.”

Unidentified maker, Rent party ticket, 1932.From the Mabel Hampton Collection, Lesbian Herstory Archives[/caption]

“We’re less interested in identifying which artists were queer,” Chauncey said, “than in showing how queer mentorship, creativity and the gay-centric friendship circles forged by these artists advanced the cultural flowering of this era.”

The businesswoman and socialite A’Lelia Walker was not herself queer, but a fierce supporter of artists and writers who happened to be. On show are her paisley-patterned fur coat and silverware used at the many soirées she hosted at her home, on loan from her great-granddaughter, the author A’Lelia Bundles. “You could say that the show is decades in the making because we have been drawing on scholarship that has existed for truly three or four decades to bring this together,” Robinson said.

Yet, according to historian Michael Henry Adams, who served as a consultant and whose photograph in the company of Renaissance-era lensman Marvin Smith is in the exhibition, stories still remain to be told. Adams wished the exhibition had made explicit the tragic deaths a year apart in the 1930s of painter duo Malvin Gray Johnson and Earle Wilton Richardson, few traces of whose love affair remain in the archives and history books today. Richardson died by suicide within a year of his loss of Johnson.

“To omit a distraught Richardson taking his own life – is that not as trivializing as it would be to suggest that Romeo’s Juliet died of a bad cold?” Adams said.

“My greatest hope for this exhibition is a simple one,” said Chauncey (not in response to Adams’ comment, made later). “That it will make it impossible for anyone, any longer, to deny or ignore that, as [Harvard professor] Henry Louis Gates once wrote, quote, the Harlem Renaissance was surely as gay as it was Black.” The Gay Harlem Renaissance | New York Historical | Running through March 8, 2026

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is a professor of media sociology at Lehman College of the City University of New York (CUNY). Follow him on Twitter @DrNickBoston and Instagram @Nick_Boston_in_New York

Mark

Mark