‘Let’s Get Lost’: Another look back at the lost beauty of jazz musician Chet Baker

Re-released for its third Film Forum run, following the original 1989 release and a 2017 revival, queer director Bruce Weber’s “Let’s Get Lost” testifies to an infatuation with fame, talent and beauty evident in every frame. Weber’s background lies in fashion and advertising photography, and he sells the hell out of his subject, jazz musician … Read More

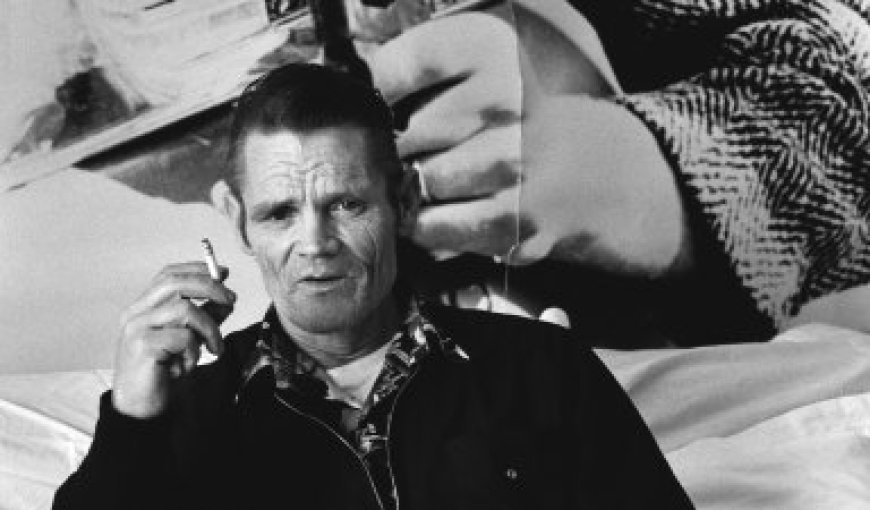

Re-released for its third Film Forum run, following the original 1989 release and a 2017 revival, queer director Bruce Weber’s “Let’s Get Lost” testifies to an infatuation with fame, talent and beauty evident in every frame. Weber’s background lies in fashion and advertising photography, and he sells the hell out of his subject, jazz musician Chet Baker. In a New York Times review, Terence Rafferty noted “It’s nominally a documentary, but it documents something that only faintly resembles reality.” “Let’s Get Lost” gives us the romantic rapture of Baker’s 1950s music, when he sang and played trumpet like an angel, and superimposes it upon the brutal, tragic arc of the rest of his life, when he became addicted to heroin and lost all his teeth. Only 57 when “Let’s Get Lost” was shot, Baker could pass for 80.

“Let’s Get Lost” still feels fresh because it avoids the clichés of music documentaries and biopics. Baker’s life story is told out of chronological order: Weber interviews him about faking mental illness to get discharged from the army as a young man, only later cutting to his introduction to the trumpet as an 11-year-old boy. Everyone involved with the film — Weber, Baker, the men and women who shared Baker’s life — recognizes its subjectivity.

“Let’s Get Lost” blurs the images and sounds of Baker’s past and present. Lush scenes of Southern California’s boardwalks and coastline jostle against stories of desperate violence. (Cinematographer Jeff Preiss did an outstanding job.) This is an act of kindness. By the end of his life, Baker’s voice had lost its sweetness, deepening and coarsening. His rendition of Elvis Costello’s “Almost Blue” demonstrates how much of his life’s darkness had entered his music, even as he clung to the same basic sound. Still, Weber granted him a glamour in the present day. He even brought Baker to the Cannes festival, where celebrities of the period hang on his arm. (Chris Isaak, who could pass for the 1950s Baker, turns up there.) Much younger women still seem attracted to him, although who knows how true this was when the camera was off?

Weber’s own attraction to the young Baker is impossible to miss. It’s a deeply erotically charged film. In the 1950s, the musician was remarkably pretty. His looks and music had an androgynous quality. More than one person likens him to James Dean. Although Baker was heterosexual, both men and women seem drawn to him. Jazz greats like Miles Davis saw him as inauthentic. While they may have perceived him as a white interloper in a genre created by Black people, he didn’t benefit from singing (in jazz, a talent usually associated with women) and performing a very accessible, pop-friendly version of the genre. But if he was seen as soft, as a person, he hardened up fast.

The first half of “Let’s Get Lost” explores the sweetness Baker once had. Then it chronicles his long downfall. Baker relates his war stories for the thousandth time. He recalls reviving a friend who OD’d at a party and getting arrested after shooting up in a gas station bathroom in Italy. In the one that changed his looks and music forever, he lost all his teeth after a beating. He tells a story in which he was robbed while going to buy drugs, while an ex-girlfriend claims that the assault came from someone fed up with “his manipulative ways.” This isn’t the first time his former partners contradict his behavior.

Given the way Baker’s life was defined by addiction and an early death, tabloid overtones are impossible to avoid. Yet at times, “Let’s Get Lost” feels gratuitously exploitative. There’s a certain relish in his downfall: Had Baker gotten in recovery and lived to his 80s, one senses Weber wouldn’t have bothered telling his life story. The film reveals a man who stole from and beat the women in his life, without coming across as a critique. During the film’s final interview session, Baker’s tired, drifting away into space. He describes himself as “sick and desperate,” looking forward to heading to Amsterdam to get methadone. Given this statement and his demeanor, it seems unlikely that he wasn’t high for these interviews. “Let’s Get Lost” seems ethically questionable in other ways too: It leaves in interview footage that a subject asked to be edited out.

Even so, it’s a film which is impossible to dismiss, as seductive as Baker’s best music. Rather than analyzing celebrity, Weber created a fever dream about it. “Let’s Get Lost” incorporates storytelling, but it leans far more on its visuals, mashing up Baker’s heavily wrinkled face and damaged voice of 1987 with his lost beauty. Weber’s images have the iconic power of jazz label Blue Note Records’ best album covers, sustained for a full two hours.

“Let’s Get Lost” | Directed by Bruce Weber | Kino Lorber | Opens at Film Forum Nov. 1st

Mark

Mark