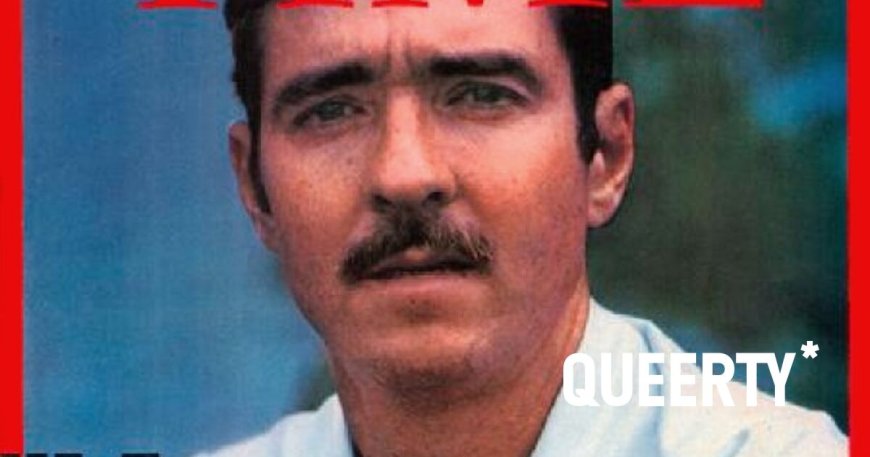

Remembering Leonard Matlovich, the gay vet who fought against homophobia in the US military… in 1975

What happened to the gay Air Force sergeant who graced the cover of Time magazine in 1975?

Veteran’s Day is a good a time to remember the hundreds of thousands of LGBTQ people who have served in the US military. Sadly, up until 2011, and despite being willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for their country, many of them were kicked out when their sexuality became known.

An estimated 114,000 people were discharged by the armed forces for homosexual conduct between the end of WWII and 2011, when federal courts lifted the ban on gays and lesbians serving.

Leonard Matlovich, a Vietnam veteran, was one of them.

Matlovich made history by gracing the cover of Time magazine on September 8, 1975. Dressed in uniform, large letters quoted Matlovich saying “I am a homosexual”. The ensuing article looked at the fledgling gay rights movement and calls for rights for gay people.

Military service and Vietnam

Matlovich was born at Hunter Air Force Base in Savannah, Georgia, in 1943. He was the only son of retired Air Force sergeant, Leonard Matlovich, and his wife Vera.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Matlovich joined the Air Force at the age of 19 and undertook three tours in Vietnam. He was seriously wounded when he stepped on a landmine. He earned a Purple Heart and the Bronze Star for heroic achievement.

Stationed back in Florida, he began to frequent local gay bars in Pensacola. He first slept with another man when he was 30 years old.

Matlovich began to come out to close friends. He also became interested in the civil rights movement. The Air Force began to utilize him to coach instructors around the country on taking race relations classes. This was in response to several racist incidents within the forces.

He later said that he began to realize the discrimination faced by gay people was not that different from that faced by ethnic minorities within the US.

Discharge and legal action

In 1974, Matlovich teamed up with the out-activist Frank Kameny and the ACLU. They decided that Matlovich, who had an unimpeachable record in the military, was the perfect candidate to launch a legal action to lift the ban on gay people serving.

In March 1975, Matlovich, then 32, delivered a letter to Langley AFB commanding officer. In it, he revealed that he was gay and wanted to continue to serve.

The Air Force first tried to get him to sign a document promising he would “never practice homosexuality again”. He refused and was duly discharged.

Matlovich refused to be ashamed or to go quietly. He gave interviews and fought to get his job back. For a brief while in the 1970s, he was the most famous out-gay person in the United States, before Harvey Milk began making headlines in San Francisco.

The late Randy Shilts remembered the impact of Matlovich’s Time cover.

“It marked the first time the young gay movement had made the cover of a major newsweekly. To a movement still struggling for legitimacy, the event was a major turning point,” Shilts wrote in his book, Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the U.S. Military.

“Little nobody me”

Matlovich spoke out at Pride events, including one in June 1975 in New York. It blew him away.

“I found myself, little nobody me, standing up in front of tens of thousands of gay people. And just two years ago I thought I was the only gay in the world. It was a mixture of joy and sadness. It was just great pride to be an American, to know I’m oppressed but able to stand up there and say so. They were very beautiful people out there,” he told Time.

Matlovich and his legal team fought his discharge. It turned into a protracted process.

Given his record, in September 1980, a US District Judge ruled Matlovich be allowed back in the Air Force. It previously had a (rarely used) ‘exception’ allowing gays to continue serving if they demonstrated exemplary service. The rule had been ditched by the military by that time but was still in effect when Matlovich served.

The Air Force then offered Matlovich compensation of $160,000. He believed that if he re-joined the service, it would have found another reason to discharge him. Matlovich also had no faith that the then-conservative Supreme Court would have backed his case. He accepted the payment.

Life and death in the 1980s

Matlovich continued to speak out in support of gay rights. In 1981, with his military compensation, he moved to Guerneville, California, and opened a pizza restaurant.

Matlovich received an HIV diagnosis in 1986 and became an activist for HIV-related issues. He was among those arrested while protesting in front of the White House lawn in June 1987. The protest was to demand the administration of Ronald Reagan do more to fight HIV.

Matlovich died on June 22, 1988, from AIDS-related illness. He didn’t live to see the arrival of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.

The Clinton-era law, which took effect in 1994, protected some gay people in the military, but an estimated 14,000 still lost their jobs before the full ban was eventually lifted in 2010 – something Matlovich had fought so many years for.

Matlovich is buried at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. He wanted his gravestone to be a memorial to all those discharged from the military because of their sexuality. It does not bear his name but instead refers to him only as a “A Gay Vietnam Veteran”. It carries the inscription, “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.”

Related:

US Air Force tweeted this Pride Month message but was then forced to turn off comments

Rep. Lauren Boebert was among those to take offense at the image.

Vintage photo shows two military men in a sweet embrace

The touching pic has been making the rounds on social media.

Mark

Mark