The art of archiving transmasculine identity

Sweatmother presents a collection of film stills from their catalog, along with an essay by Ellis Jackson Kroese. WORDS ELLIS JACKSON KROESE IMAGES COURTESY OF SWEATMOTHER EXCERPT AND SPREADS FROM… The post The art of archiving transmasculine identity appeared first on GAY TIMES.

Sweatmother presents a collection of film stills from their catalog, along with an essay by Ellis Jackson Kroese.

WORDS ELLIS JACKSON KROESE IMAGES COURTESY OF SWEATMOTHER EXCERPT AND SPREADS FROM AFM WITH THANKS TO FEELD

A new addition to the landscape of literature – enter Issue 001 of AFM, Feeld’s new print magazine edited by Maria Dimitrova and Haley Mlotek, which launches today.

Below, we publish an exclusive excerpt.

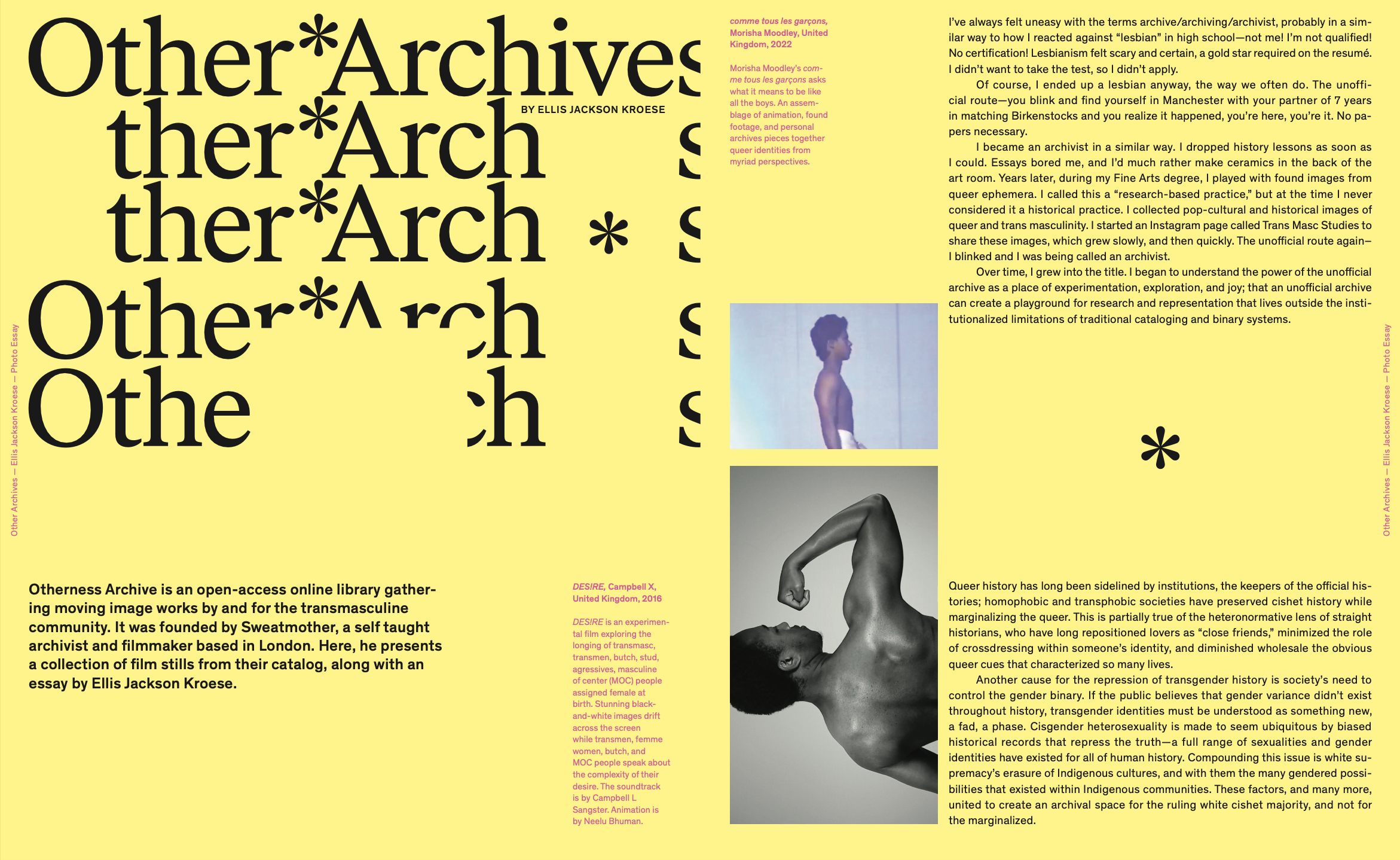

Otherness Archive is an open-access online library gathering moving image works by and for the transmasculine community. It was founded by Sweatmother, a self taught archivist and filmmaker based in London. Here, he presents a collection of film stills from their catalog, along with an essay by Ellis Jackson Kroese.

I’ve always felt uneasy with the terms archive/archiving/archivist, probably in a similar way to how I reacted against “lesbian” in high school—not me! I’m not qualified! No certification! Lesbianism felt scary and certain, a gold star required on the resumé. I didn’t want to take the test, so I didn’t apply.

Of course, I ended up a lesbian anyway, the way we often do. The unofficial route—you blink and find yourself in Manchester with your partner of 7 years in matching Birkenstocks and you realise it happened, you’re here, you’re it. No papers necessary.

I became an archivist in a similar way. I dropped history lessons as soon as I could. Essays bored me, and I’d much rather make ceramics in the back of the art room. Years later, during my Fine Arts degree, I played with found images from queer ephemera. I called this a “research-based practice,” but at the time I never considered it a historical practice. I collected pop-cultural and historical images of queer and trans masculinity. I started an Instagram page called Trans Masc Studies to share these images, which grew slowly, and then quickly. The unofficial route again – I blinked and I was being called an archivist.

Over time, I grew into the title. I began to understand the power of the unofficial archive as a place of experimentation, exploration, and joy; that an unofficial archive can create a playground for research and representation that lives outside the institutionalised limitations of traditional cataloging and binary systems.

Queer history has long been sidelined by institutions, the keepers of the official histories; homophobic and transphobic societies have preserved cishet history while marginalising the queer. This is partially true of the heteronormative lens of straight historians, who have long repositioned lovers as “close friends,” minimised the role of crossdressing within someone’s identity, and diminished wholesale the obvious queer cues that characterised so many lives.

Another cause for the repression of transgender history is society’s need to control the gender binary. If the public believes that gender variance didn’t exist throughout history, transgender identities must be understood as something new, a fad, a phase. Cisgender heterosexuality is made to seem ubiquitous by biased

historical records that repress the truth—a full range of sexualities and gender identities have existed for all of human history. Compounding this issue is white supremacy’s erasure of Indigenous cultures, and with them the many gendered possibilities that existed within Indigenous communities. These factors, and many more, united to create an archival space for the ruling white cishet majority, and not for the marginalised.

Recently, however, many major museums have scrambled to make up for their centuries of oppression and silencing — rewriting biographies to include the queerness they previously erased, publicly lamenting those missing from the archive, and proudly displaying the few objects with queer provenance that they could find in the vaults.

To me, it rarely feels enough. It often feels too reactionary, too forced. It is not our own. When museums have been a space of oppression and reduction, we must create an expansive safe space to write our own history. We must create our own canon, our own vaults.

“Sometimes archiving is studied and sometimes it evolves organically, informally”

Sometimes archiving is studied and sometimes it evolves organically, informally. In this space of possibility, other archives are created; the archives that develop in the dark, the archivists that learn as they go. The messy archives with the cheap gloves, the digital archives with the shitty organisational system. The archives that were birthed from nothingness by somebody, anybody, who found something worth remembering. People who get swallowed by research wormholes and end up somewhere they never expected. People who created something and stored it away.

Garages are filled with queer erotica, dropboxes created to store and share scans of ephemera, screenings curated to show the unseen. These types of archives are created by artists, by collectors, by organizers, by anyone. It is a lawless land, in which collections develop outside of institutions, purely for the sake of documenting and gathering.

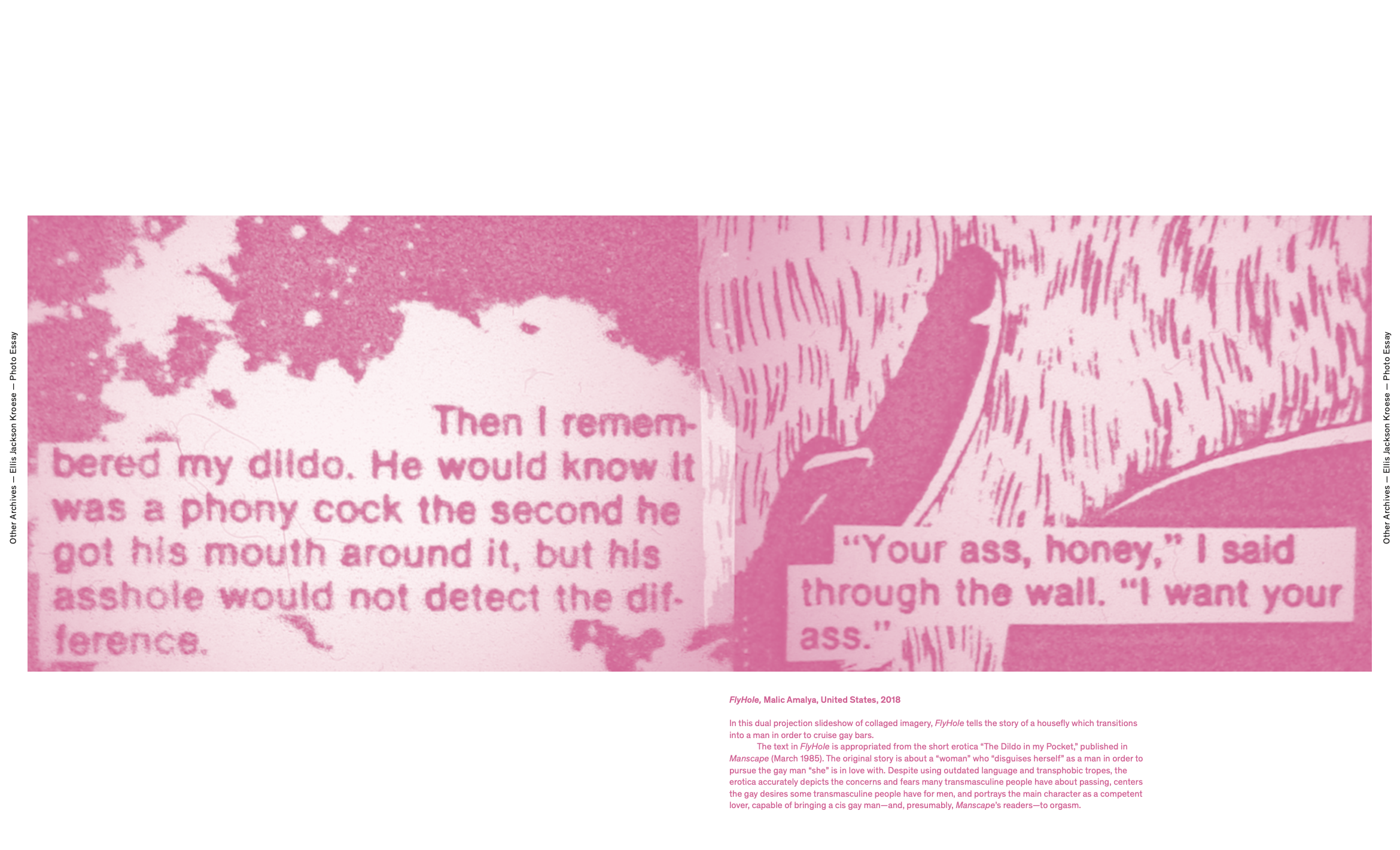

It is this type of grassroots archiving that is explored by Otherness Archive, an open-access, online library gathering and moving image works “by and for,” the transmasculine community. Here, anyone with an internet connection and some free time can explore transgender arts and culture. The archive was founded by Sweatmother in January 2023, and was created in partnership with a small group of trans researchers and archive builders.

Since then, it has become a living, ever-evolving organism with submissions and suggestions from the community regularly updating the collection. Approximately 500 films are currently available through the archive. It holds experimental arthouse videos, filmed speeches by famous activists, erotica, indie documentaries, home movies. It holds our community, our history, our siblings, our transcestors.

To describe such collections as archives can be controversial; to describe one-self as an archivist without the proper accreditation might seem hubristic. And yet it empowers those who collect, those who donate, those who care about the complex and marginal truth. It allows limits to be pushed in a way that perhaps government or cultural institutions wouldn’t fund. It allows freedom from those in power, who have a stake in our binary heteronormative system.

Self-made archives are created to represent ourselves authentically—to give parts of our community to future generations. They are created to understand ourselves as individuals amongst a whole; to reflect on what it means to be, to live, to hurt, to want, to be alone, to be together. They are created to give gravitas, they are created to give context, they are created to give joy. They are created to give perspective, silliness, community, inspiration, love, love, love.

They are ours.

See spreads from this feature in AFM below.

The post The art of archiving transmasculine identity appeared first on GAY TIMES.

Mark

Mark