This groundbreaking queer activist’s childhood home is a National Landmark you can visit

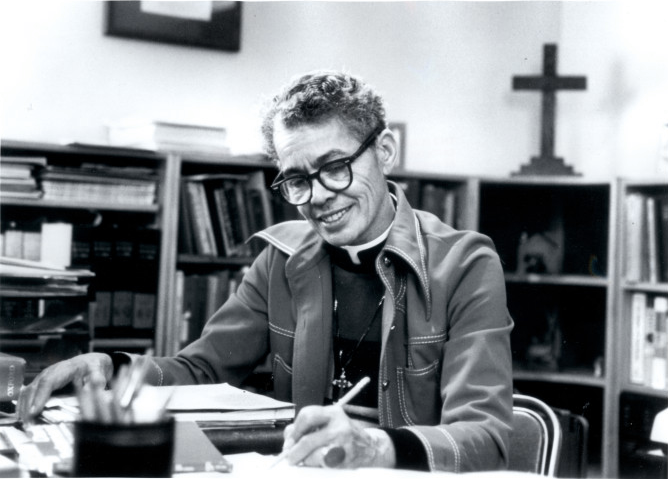

Despite a life decorated with achievements, nothing ever came easy for Pauli Murray.

Before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Alabama in 1955, 30-year-old Pauli Murray and a friend took a similar stand in 1940 during an interstate trip from New York to North Carolina. Rather than make headlines, Murray temporarily landed in jail.

Still, it marked just the beginning of their fight against Jim Crow laws and oppression in all its forms. Their legacy would be remembered as a “mother to feminist legal strategy,” including serving as the credited inspiration for the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to change the course of women’s rights with the historic Supreme Court case Reed v. Reed.

Pack your bags, we’re going on an adventure

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for the best LGBTQ+ travel guides, stories, and more.

Subscribe to our Newsletter today

Murray was born Anne Pauline on November 20, 1910, in Baltimore as the fourth of six children. Her mother died from a massive cerebral hemorrhage when s/he was three years old, and debilitating grief transformed their father from a respected public school principal to a patient at an insane asylum for people of color, where a guard in the basement of the hospital later murdered him.

Although this series of tragic events left Murray a vulnerable orphan, they would remember this phase of their life as “the most significant fact of my childhood.” Thankfully, they found a sense of home at her aunt’s in Durham, where they lived until 16.

For many queer people, it was Murray’s internal struggle with their identity that was most relatable, even though it was a journey most had to take alone during one of the most homophobic eras in history. Perhaps this is why Murray left it out of their biography. During the 1930s, they changed their name to “Pauli” and sought gender-affirming treatments, including hormone therapy, but were denied.

Pauli Murray College at Yale reports that most of Murray’s intense romantic relationships were with women.

Murray wielded the power of multiple identities in all aspects of their life. They wrote poetry that was published in The Crisis, a publication of the NAACP. They exchanged letters about racism in America with Eleanor Roosevelt (originally writing the president) and weaponized their poignant lyricism to deliver empowering speeches across the country advocating for civil rights. A speech in Richmond led a Howard Law professor, who heard them speak, to encourage Murray to apply and provide a scholarship.

According to the Women’s History Museum, “In a 1944 paper, Murray proposed challenging the ‘separate’ part of the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) Supreme Court decision as a violation of the 13th and 14th Amendments; this argument eventually formed the basis for the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) case,” which, as a refresher, eradicated segregation.

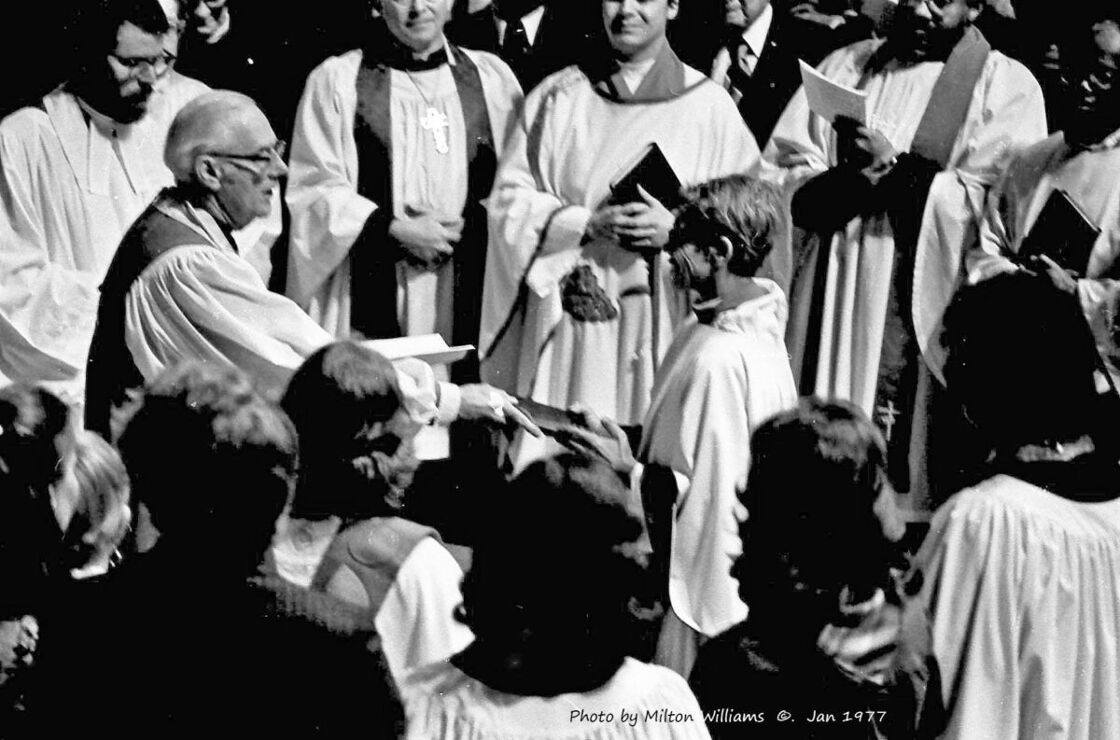

Murray faced prejudice in all aspects of their life for being an African American queer woman and spent their life advocating for civil rights, carrying all those torches without letting any of them fumble. They put their activism to legal paper. Murray helped found the National Organization for Women (NOW) and became the first ordained African-American female priest in the Episcopal Church.

Despite a life decorated with achievements for advancing equality, nothing ever came easy for Murray. Their marginalization, coupled with their vocal activism when much of the world stood silent on hate, made it difficult for them to sustain jobs, and they lived from place to place. Murray refused to compromise any aspect of their humanity.

That fact makes it fitting that their groundbreaking legacy was immortalized in the only place they ever found home: at their aunt’s house in North Carolina. The structure, built by their Fitzgerald grandparents in 1989, was designated a National Treasure in 2015 and a National Historic Landmark in 2016.

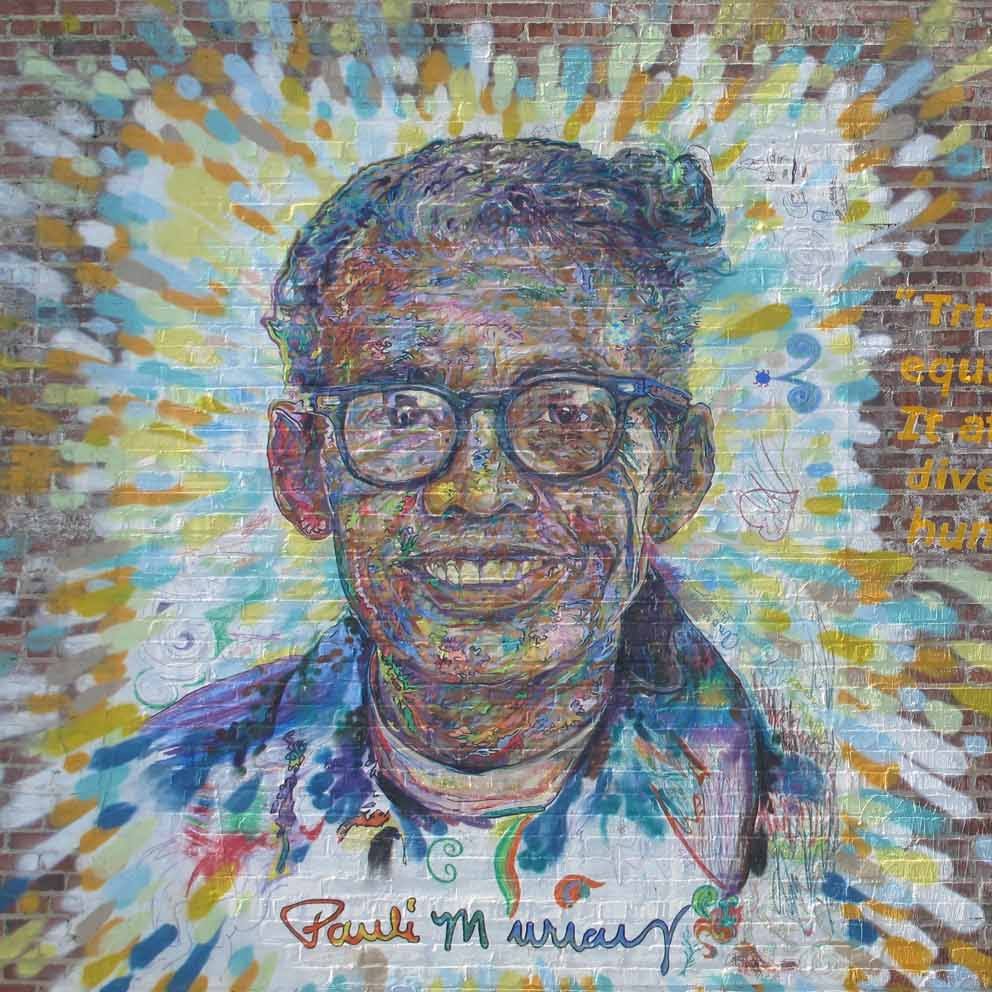

Nowadays, locals cherish it as the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, one of many buildings dedicated to their memory. But it is the only one with direct ties to the multi-hyphenate activist. “Exhibits, community dialogues, visual and performing arts, activism, and workshops at the Center connect history to contemporary human rights issues.”

Susan Ware, Editor, Notable American Women: a Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century, summarizes Murray’s significance: “It may be that when historians look back at 20th century American history, all roads will lead to Pauli Murray . . . Civil rights, feminism, religion, literature, law, sexuality – no matter what the subject, there is Pauli Murray.”

If one queer person overcame all the odds stacked against them and used academia to battle violent bigotry, then it’s up to the rest of us to carry on their teachings and uplift each other’s greatness. And to honor Murray’s spiritual home.

Mark

Mark