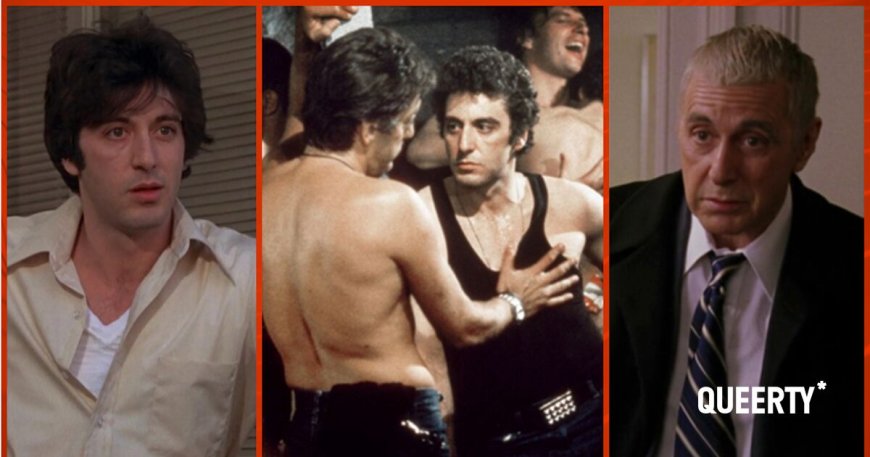

You Don’t Know Al: Why Al Pacino’s career is a lot more queer-coded than many people think

Acting legend Al Pacino helped redefine masculinity on screen with a number of queer and queer-adjacent roles.

For many, it’s likely Al Pacino’s career is defined by two towering characterizations: the college boy turned mafia boss Michael Corleone in The Godfather trilogy—described as “arguably cinema’s greatest portrayal of the hardening of a heart”—and Tony Montana, the bombastic Miami drug lord of Scarface, who went out in a blaze of guns and a mountain of cocaine.

But Pacino—a stage actor who spent his 20s cutting his teeth in the theater world before catapulting to film stardom—has embodied a spectrum of characters across his career, defining and re-defining modern masculinity on screen.

In addition to playing the bisexual Sonny Wortzik in Dog Day Afternoon (a radical career choice for a male movie star at the top of his game in the mid-1970s), his filmography contains a number of films that feature gay characters or, at the very least, queer subtext. Not to mention: his first stage kiss in the role that won him a Tony Award was with another man!

Also notable is the way Pacino’s characters react to accusations of homosexuality (and there are several). From Tony Montana to Frank Serpico to Bobby Deerfield, when a character’s sexuality is questioned, they deflect with humor, or otherwise seem utterly unfazed—never defensive or insulted. From an acting standpoint, that seems to be a conscious choice on Pacino’s part.

When asked in 2014 why he’s chosen to star in so many films with LGBTQ+ themes, Pacino responded, “I don’t know, it’s the world we live in, it’s life[…] it’s the world I’ve lived through. It’s a very accepted thing throughout my life, so it’s a natural thing.”

Ahead of the release of Pacino’s new memoir, Sonny Boy (out October 15 from Penguin Random House) we’re re-examining 10 notable roles from the acting legend’s filmography through a queer lens.

Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Dog Day Afternoon is based on the true story of John Wojtowik (named Sonny in the movie), who robbed a Brooklyn bank in order to pay for his wife’s gender confirmation surgery. As we find out, Sonny is not only married to Angie, the mother of his children, but Leon (Chris Sarandon), a trans woman based on Elizabeth Eden.

In one of the film’s most touching scenes, Pacino dictates his last will and testament to the bank manager: “To my darling wife, Leon, whom I love more than any other man has loved another man in all eternity … To my wife, my sweet wife Angela … you are the only woman that I ever loved.”

Rewatching Dog Day Afternoon in 2024 does raise the question: can Sonny still be considered a canonically queer or bisexual character, if he was married to two women? What’s certain is that the character Pacino and Lumet created is unconcerned with labels or public perception. He loves who he loves, fiercely—and he’s willing to sacrifice himself so they can live a better life.

Cruising (1980)

Directed by William Friedkin (The Exorcist), Cruising was a controversial film and critical flop that raised the ire of the New York queer community before it even started filming. Pacino plays Steve Burns, a cop assigned to go undercover in New York’s gay S&M scene to track down a serial killer because he fits the profile of the men being killed.

The film—which was panned for its eerie, inconclusive ending—calls into question Burns’ own sexuality and even his role in the murders. As Burns throws himself into the club scene, he’s cautious but nonjudgmental, and willing to be put into uncompromising positions. He’s upset by the homophobia and brutality he sees from his fellow police officers, and at one point even tries to quit the assignment.

The first printed interview Pacino ever gave, eight years and five Oscar nominations into his career, took place during the filming of Cruising. When asked what he thought about the pushback, Pacino said, “It never dawned on me that it would provoke those kinds of feelings. I’m coming from a straight point of view, and maybe I’m not sensitive enough in that area. But they are sensitive to the situation, and I can’t argue with that.” He continued: “If the gay community feels the film shows them in a bad light, then it is good they are protesting, because anything that raises consciousness in this area is all right.”

Related

Controversial as it may have been, erotic thriller ‘Cruising’ captured something true about leather bars

One thing’s for sure about the late, great director William Friedkin: He did his homework.

Sea Of Love (1989)

The sexy neo-noir Sea Of Love marked Pacino’s return to the big screen after a four-year hiatus. His character, Frank Keller, is a depressed, alcoholic detective who teams up with his partner Sherman Touhey (John Goodman) to capture a serial killer, whom they suspect is a single woman. They set up a sting operation by placing a personal ad and scheduling dates with every woman that responds. While on the phone with a potential date, Pacino says: “You like guys or girls? Oh, that’s cool. Me? Well, sometimes, you know, but mainly girls.” Although it may have just been a throwaway line, it’s made Keller a canonically bi character—at least according to an X post (seen above) that circulated on this year’s Bisexual Visibility Day.

Scarecrow (1973)

In this restless and heartbreaking film, Pacino plays Francis “Lion” Lionel Delbuchi, a drifter who links up with Gene Hackman’s ex-con Max to traverse the country. While not an overtly queer film, there are several moments that speak to the blurry dynamics that can emerge within male friendships. In one scene, Pacino tries to dance with Hackman: he grabs his waist and spins him around, innocently motivated by pure instinct, while Hackman appears uncomfortable. In a later scene, Hackman performs a slow striptease in the middle of a bar, as the bar’s male patrons jeer, laugh, and applaud. Their reactions are juxtaposed with Lion’s, who sits alone in the back of the room, stone faced. We don’t know what he’s thinking—could it be jealousy? Is it yearning? Perhaps the ambiguity is the whole point.

Heat (1995)

In the words of comedian Chris Fleming, “Heat is a closeted classic…it’s a film about Al Pacino and Robert DeNiro lusting after each other and it’s set to a synth score that makes me want to crash my car.” The ’90s neo-noir pits Neil McCauley (DeNiro), a tightly coiled career criminal, against Vincent Hanna (Pacino), a brilliant but cocaine-addled LAPD detective.

In the film’s climax, Hanna finally catches up with McCauley in a Los Angeles diner. This famous scene marked, shockingly, the first time Pacino and DeNiro acted opposite each other on camera. Pacino, with his theatrical roots, wanted to rehearse the scene multiple times, but DeNiro pushed back: he wanted the novelty and spontaneity of the moment to feel as real as possible. What resulted was a sublime tension, as the two men gingerly, tenderly open up to one another—wary of revealing too much, while also sensing that the man across the table might be the only other person who truly understands him.

Angels In America (2003)

Pacino won both an Emmy and Golden Globe for playing Roy Cohn, the notorious lawyer who served as both Joseph McCarthy’s chief counsel and Donald Trump’s mentor before he died of AIDS. Cohn’s first scene is a tour-de-force as Pacino intimidates a baby-faced Patrick Wilson, while feasting on Kushner’s dialogue. It’s a masterful comedic performance, and he plays Cohn’s vile and menacing side just as convincingly, such as when he delivers a virulently homophobic monologue denying he has AIDS, while admitting to having sex with men. In his 2004 Golden Globe acceptance speech, Pacino said: “What can I say about Tony Kushner’s creation of Roy Cohn? It is a part that every actor dreams to play, and it has all the multi-faceted, interesting dimensions that actors really live for.”

Related

Tony Kushner’s ‘Angels in America’ remains prescient 25 years later

The playwright who changed drama with ‘Angels in America’

…And Justice For All (1979)

In Norman Jewison’s …And Justice For All, a tragicomic critique of the American legal system, Pacino plays Arthur Kirkland, a lawyer who increasingly finds his career successes at odds with his basic humanity. While Kirkland himself is not queer, he has a poignant subplot with Ralph Agee, a Black transgender woman whom he first sees entering lockup. He later represents her, but has to miss her court date. His colleague fumbles her trial and Agee is sent back to jail, where she hangs herself. Pacino’s rage after finding out Agee’s fate is wild and devastating. “They’re people, Warren, you know? They’re people! They’re just people!” he screams, tears in his eyes. It’s a pivotal scene in the movie and in the evolution of Kirkland’s consciousness—and one of Pacino’s finest, if underrated, onscreen moments.

The Devil’s Advocate (1997)

The Devil’s Advocate is most notable for Pacino’s deliciously hammy performance as John Milton, the titular devil, and Keanu Reeves’ inability to maintain a consistent Southern accent from scene to scene. Pacino’s Milton is lecherous and never without a female companion, but for him, sex is simply a form of power and tool for manipulation—who knows who, or what, he’s actually attracted to. And his climactic monologue on God, sin, and the concept of free will, is gloriously campy. At one point, he even starts lip-syncing Frank Sinatra’s “It Happened in Monterey,” something Pacino improvised. With this purposefully over-the-top, scenery-chewing performance, it’s possible that the Devil qualifies as a quintessentially queer-coded villain.

Scarface (1983)

Like Scarecrow, Scarface can be read as a study of complex power dynamics within male friendships. Tony Montana and his right-hand man Manolo Ribera (Stephen Bauer) rise to power together—there is no Tony without Manny, and vice versa. While both characters are written as heterosexual to the point of parody, one has to ask: is it all part of the performance required to assimilate and dominate? And *spoiler!* Tony turns lethal when Manny expresses his feelings for Tony’s kid sister Gina. We assume that he’s being protective of Gina, but could it be that Tony is even more possessive of Manny? When you see the feral look in Pacino’s eyes just before he shoots Bauer, it seems entirely possible.

Bobby Deerfield (1977)

Bobby Deerfield—a film about a disillusioned racecar driver who falls in love with a terminally ill woman—was Pacino’s first critical disappointment after a run of Oscar-nominated roles. In one scene, Lillian observes that Bobby is a gentle, feminine man and asks him if he’s gay; she then clarifies she has nothing against gay people. “Well, that’s good,” Pacino deadpans. Later, Bobby performs an impersonation of Mae West for Lillian, in an effort to reveal something about himself that will surprise her. Hands on hips, he chirps: “Come up and see me sometime, big boy.” It’s a brief scene, but this often overlooked character in Pacino’s oeuvre is notable for his easy embrace of his feminine side—and Pacino has cited the role as one of his favorites.

Related

This dogged crime tale was one of the first—and best—films to bring queerness to the Oscars

1975’s ‘Dog Day Afternoon’ was one of the first films with LGBTQ+ themes ever nominated for an Oscar.

Mark

Mark