Native Queers Are Taking Back Paradise

There are few artists who’ve shaped Westerners’ visions of the island paradise as much as the Postimpressionist French painter Paul Gauguin, who spent time in Tahiti and other locations in French Polynesia more than a century ago. And yet Gauguin was himself seduced by the romantic idea of the island Eden presented through Western cultural works like 1719’s Robinson Crusoe.One of the first British novels ever published, Crusoe is, essentially a story of colonization — as Elif Batuman notes in a recent issue of The New Yorker — focusing on an Englishman exploiting the natural and human resources of an island. Batuman points to Edward Said’s 1993 book of essays, Culture and Imperialism, to suggest the novel — as a format of literature — is inherently and symbiotically bound to imperialism. Tourism probably holds a similar symbiosis with colonialization, historically bringing Europeans to island communities and developing nations. Many of these are still being exploited for their resources, even if those resources are now sometimes intangible. In “Constructing Paradise in the Western Imagination: Reflections on Colonial Legacies and Developing Nations’ Tourist Industries,” Jamaican artist and scholar Oneika Russell writes, “One could argue that without paradise, tourists might not be able to bear the burdens associated with its own man-made systems and structural socio-economic and political problems.”Having long ago stripped their own lands of resources, most empires can only be sustained by exploiting those of others. Today one of those resources may be the replenishing effect that travel can provide.As a visual artist, Russell writes elsewhere, “My work often investigates the trope of the fetishized and mythologized native within the paradigm of ‘paradise’ and tourism industries.” In “Constructing Paradise,” Russell describes her series “After Gauguin” as an examination of the connection between “exoticism and the colonial, Western and European fascination with places like Tahiti and Jamaica.”And yet Russell acknowledges, “When he arrived in Tahiti, [Gauguin] was disappointed. It was too colonized and settled. It was not quite the primitive land of his dreams.”The Polynesian islands Gauguin visited and the subjects he painted were also not quite what consumers of his paintings wanted to see. They were too multidimensional and too queer. So Gauguin subtly painted those parts out of the picture — but he couldn’t entirely erase the queerness of his inspiration. Three Fa’afafine (After Gauguin) by Yuki KiharaIn turn, the French painter inspired Sāmoan-Japanese artist Yuki Kihara’s own “After Gauguin” series, presented in the critically acclaimed “Paradise Camp” exhibit at 2022’s Venice Biennale. Kihara told Cristina Verán of Cultural Survival Quarterly that when she first saw Gauguin’s paintings, “I recalled an essay written by [Māori] Professor Emerita Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, which discussed the models of Gauguin paintings as being māhū, the Tahitian third gender.”Kihara herself identifies as fa’afafine, which translates to “in the manner of a woman” and describes Sāmoa’s third gender. She said Gauguin’s “figures reminded me of my fa’afafine friends, as the landscapes also reminded me of home. I would later discover that Gauguin had actually used photographs of people and places in Sāmoa as inspiration.” Yuki Kihara with images from her Paradise Camp show (photo by Luke Walker)Those figures would also feel familiar to many Hawaiians. DeSoto Brown, historian at O‘ahu’s Bishop Museum, recently curated an exhibit sharing the story of four powerful trans healers who traveled from Tahiti to Hawai‘i around the 1500s. Brown explains that “there was a period in Hawaiian history where there was actually regular visitation between Tahiti and Hawai‘i. And this is not a small thing to do.”The two Polynesian island nations are roughly 2,630 miles apart. (That’s even farther than Hawai‘i is from California, which is 2,470 miles away.)“It’s an arduous journey,” Brown says, especially when made in a double-hulled Polynesian voyaging canoe before the invention of navigating equipment. The visitors from Tahiti “are said to have been māhū,” Brown continues. “They were transgendered.” Before these dual male and female spirits left the islands they imbued their powers into four monoliths, which stood on the shores of O‘ahu for generations until colonizers buried them. Today, the recovered healer stones are located along one of the busiest stretches of Waikiki Beach, but few know their stories. The 2021 animated short film The Healer Stones of Kapaemahu hoped to change that. It did spark a subsequent museum exhibit.In “Paradise Camp,” Kihara wanted to tell the stories of Sāmoans and reclaim her island from Gauguin’s distortions. “In order to disrupt Gauguin’s heteronormative view of paradise,” she explained, “I chose to deploy an exaggerated, camp aesthetic, sho

There are few artists who’ve shaped Westerners’ visions of the island paradise as much as the Postimpressionist French painter Paul Gauguin, who spent time in Tahiti and other locations in French Polynesia more than a century ago. And yet Gauguin was himself seduced by the romantic idea of the island Eden presented through Western cultural works like 1719’s Robinson Crusoe.

One of the first British novels ever published, Crusoe is, essentially a story of colonization — as Elif Batuman notes in a recent issue of The New Yorker — focusing on an Englishman exploiting the natural and human resources of an island. Batuman points to Edward Said’s 1993 book of essays, Culture and Imperialism, to suggest the novel — as a format of literature — is inherently and symbiotically bound to imperialism.

Tourism probably holds a similar symbiosis with colonialization, historically bringing Europeans to island communities and developing nations. Many of these are still being exploited for their resources, even if those resources are now sometimes intangible.

In “Constructing Paradise in the Western Imagination: Reflections on Colonial Legacies and Developing Nations’ Tourist Industries,” Jamaican artist and scholar Oneika Russell writes, “One could argue that without paradise, tourists might not be able to bear the burdens associated with its own man-made systems and structural socio-economic and political problems.”

Having long ago stripped their own lands of resources, most empires can only be sustained by exploiting those of others. Today one of those resources may be the replenishing effect that travel can provide.

As a visual artist, Russell writes elsewhere, “My work often investigates the trope of the fetishized and mythologized native within the paradigm of ‘paradise’ and tourism industries.” In “Constructing Paradise,” Russell describes her series “After Gauguin” as an examination of the connection between “exoticism and the colonial, Western and European fascination with places like Tahiti and Jamaica.”

And yet Russell acknowledges, “When he arrived in Tahiti, [Gauguin] was disappointed. It was too colonized and settled. It was not quite the primitive land of his dreams.”

The Polynesian islands Gauguin visited and the subjects he painted were also not quite what consumers of his paintings wanted to see. They were too multidimensional and too queer. So Gauguin subtly painted those parts out of the picture — but he couldn’t entirely erase the queerness of his inspiration.

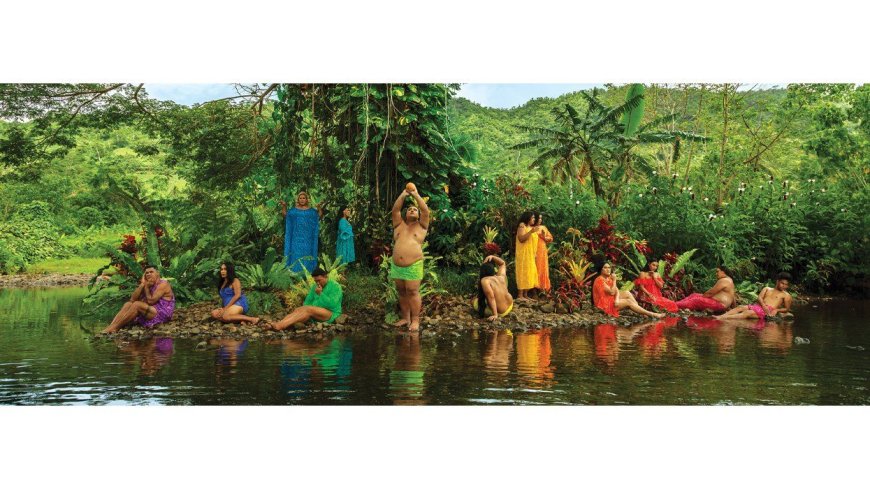

Three Fa’afafine (After Gauguin) by Yuki Kihara

Three Fa’afafine (After Gauguin) by Yuki Kihara

In turn, the French painter inspired Sāmoan-Japanese artist Yuki Kihara’s own “After Gauguin” series, presented in the critically acclaimed “Paradise Camp” exhibit at 2022’s Venice Biennale. Kihara told Cristina Verán of Cultural Survival Quarterly that when she first saw Gauguin’s paintings, “I recalled an essay written by [Māori] Professor Emerita Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, which discussed the models of Gauguin paintings as being māhū, the Tahitian third gender.”

Kihara herself identifies as fa’afafine, which translates to “in the manner of a woman” and describes Sāmoa’s third gender. She said Gauguin’s “figures reminded me of my fa’afafine friends, as the landscapes also reminded me of home. I would later discover that Gauguin had actually used photographs of people and places in Sāmoa as inspiration.”

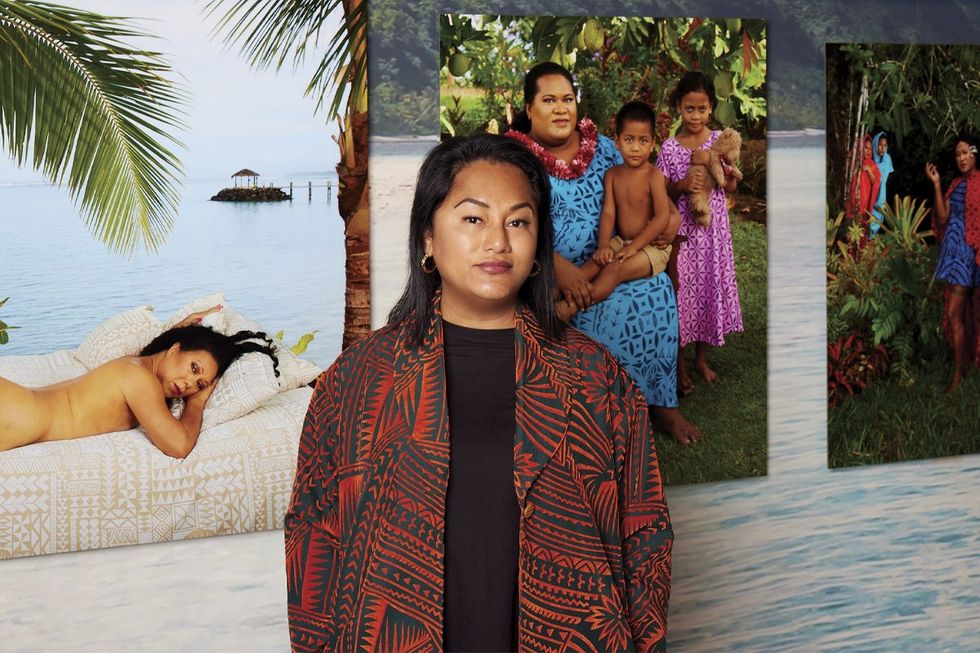

Yuki Kihara with images from her Paradise Camp show (photo by Luke Walker)

Yuki Kihara with images from her Paradise Camp show (photo by Luke Walker)

Those figures would also feel familiar to many Hawaiians. DeSoto Brown, historian at O‘ahu’s Bishop Museum, recently curated an exhibit sharing the story of four powerful trans healers who traveled from Tahiti to Hawai‘i around the 1500s. Brown explains that “there was a period in Hawaiian history where there was actually regular visitation between Tahiti and Hawai‘i. And this is not a small thing to do.”

The two Polynesian island nations are roughly 2,630 miles apart. (That’s even farther than Hawai‘i is from California, which is 2,470 miles away.)

“It’s an arduous journey,” Brown says, especially when made in a double-hulled Polynesian voyaging canoe before the invention of navigating equipment.

The visitors from Tahiti “are said to have been māhū,” Brown continues. “They were transgendered.” Before these dual male and female spirits left the islands they imbued their powers into four monoliths, which stood on the shores of O‘ahu for generations until colonizers buried them. Today, the recovered healer stones are located along one of the busiest stretches of Waikiki Beach, but few know their stories. The 2021 animated short film The Healer Stones of Kapaemahu hoped to change that. It did spark a subsequent museum exhibit.

In “Paradise Camp,” Kihara wanted to tell the stories of Sāmoans and reclaim her island from Gauguin’s distortions. “In order to disrupt Gauguin’s heteronormative view of paradise,” she explained, “I chose to deploy an exaggerated, camp aesthetic, showing paradise instead from a fa’afafine perspective. This re-directing of his paintings toward their original inspiration became a process of reclaiming the narrative.”

Three Fa’afafine (After Gauguin) by Yuki Kihara

Three Fa’afafine (After Gauguin) by Yuki Kihara

One of her photographs, Fonofono o le nuanua: Patches of the rainbow (opening image), features a group of fa’afafine posing riverside. The models are members of the Aleipata Fa’afafine Association, who were also first responders in the devastating aftermath of the 2009 tsunami. Choosing them for the project reiterates the way the (queer) people living in paradise have less luxurious lives than tourism marketing might suggest.

Indeed, the lives of LGBTQ+ residents of color are often starkly divergent from the experiences of queer travelers. In a 2022 roundtable discussion, “Black, Queer & Trans: Mobilizing in the Caribbean and Beyond,” hosted by the Barnard Center for Research on Women, Jamaican trans women Kymm Foster from TransWave Jamaica and Emani Edwards of Connek JA joined Chaday Emmanuel of Connek JA to speak about facing poverty and discrimination. Despite hailing from a vacation destination, Foster is “never at liberty to just rest” and said, “We don’t know what vacation is.” Emmanuel added she wasn’t even allowed into entertainment spaces in Jamaica because of “how I dressed.”

Other island natives share similar stories of living in poverty in paradise. Drag performer Ana Macho told Global Press Journal her original song “Blin Blin” is “about the paradise that Puerto Rico is, but the one who lives here can’t live it.” The native Puerto Rican identifies as nonbinary and is among the queer musicians finding their voices in reggaeton. “It’s a genre of music that’s tightly tied to irreverence,” Macho explained. “And that attracts many oppressed bodies: feminine bodies, queer bodies.”

Oppression can be exhausting, but it can also spark creativity. Jamaica’s multitalented entrepreneur Emmanuel responded to the exclusion she faced at clubs and parties by launching her own inclusive spaces, including Jamsterdam, Tribe876, and Tribe Tours. Now Connek JA organizes events, media, and travel experiences that bring together queer family and allies across borders.

DeVonn Francis, a gay Jamaican American says Connek JA creates travel opportunities for queer Caribbean people living in the U.S. to visit the islands. “So that people who are within the diaspora can go back to Jamaica, create these networks so that people have their own channels of resources, and connect in the way that they want to versus that being dictated to them.”

“It belongs to us,” Foster said in the roundtable. She was talking about trans creative talent, but she could have just as easily been speaking about the island itself. “We are owed when you take it.”

Mark

Mark