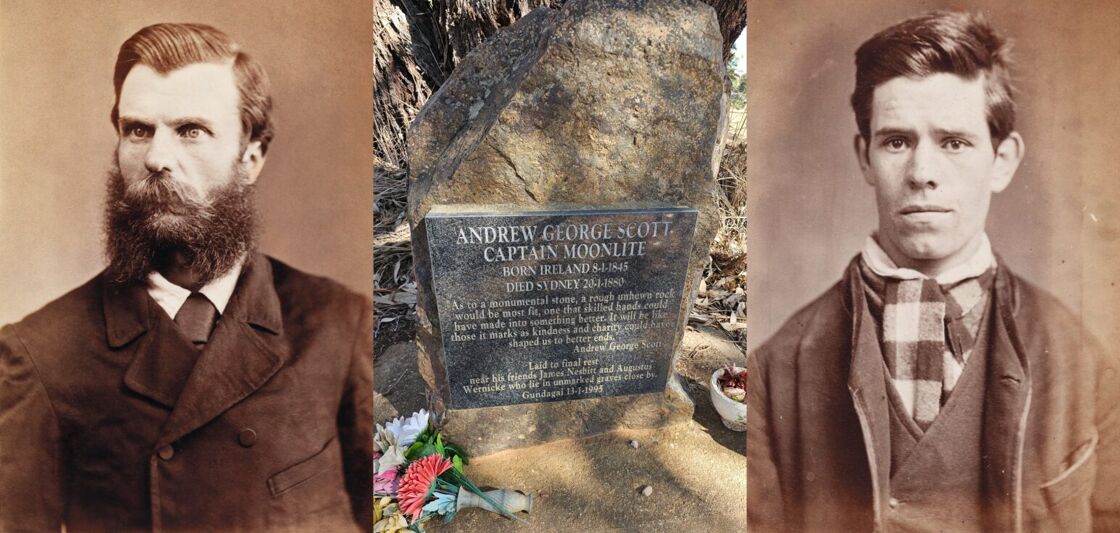

How the graves of a legendary Australian outlaw and his sexy soulmate became a heritage site

New South Wales has recognized the unlikely shared resting place of Captain Moonlite and his beloved James Nesbitt.

It was late 1879 in the Australian outback, and Captain Moonlite and his gang of young bushrangers were desperate and on the brink of starvation. Depending on who you believe, they’d come to Wantabadgery Station—roughly halfway between Sydney and Melbourne—either on the unkept promise of work, or with the full intention of robbing the locals.

Whatever their motives, Moonlite and his hungry men stormed the little settlement and its surrounding businesses, stealing supplies and booze and taking 25 prisoners. A shootout with law enforcement ensued, during which a police constable was mortally wounded—as was Moonlite’s beloved gang member, James Nesbitt. Local newspaper reports at the time said that Moonlite wept over Nesbitt “like a child, laid his head upon his breast, and kissed him passionately.”

Later letters from Moonlite revealed that he and Nesbitt shared a deep connection that was clearly more than just an intense bromance. “My dying wish is to be buried beside my beloved James Nesbitt, the man with whom I was united by every tie which could bind human friendship,” he wrote. “We were one in hopes, in heart and soul, and this unity lasted until he died in my arms.”

Pack your bags, we’re going on an adventure

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for the best LGBTQ+ travel guides, stories, and more.

Subscribe to our Newsletter today

Related

Inside the unlikely reinvention of Mexico’s most infamous prison for gay men

Mexico’s General Archive, once a notorious prison, has a gay past that impacts the country’s LGBTQ+ community to this day.

Bushrangers were to Australians what Wild West outlaws were to Americans, a motley assortment of frontier bandits, largely in the 19th century, who despite the gravity of their crimes have come to represent Robin Hood-like bad-boy heroes in the collective national consciousness.

In terms of contemporary infamy in 1879, Captain Moonlite was not yet a top-tier bushranger on par with the notorious Ned Kelly, but he was well on his way. Andrew George Scott was born in Ireland in 1842, and he came to Australia in 1868 by way of New Zealand. Ostensibly a lay preacher studying for the Anglican priesthood, Scott conducted his first bank heist the following year in the gold mining town of Mount Egerton, leaving a note behind meant to throw authorities off the track, signed with the intentionally misspelled moniker Captain Moonlite.

While in

In the months that followed, Scott simultaneously embarked on a speaking tour urging

After the Wantabadgery shootout in November 1879, Scott was arrested and taken to Sydney’s Darlinghurst Gaol, where he and fellow surviving gang member Thomas Rogan were both hanged for the murder of Constable Bowen on January 20, 1880. Scott went to the gallows wearing a lock of his beloved Nesbitt’s hair on his finger.

Scott’s dying wish to be buried next to his “dearest Jim”—who had been unceremoniously entombed near their last shootout in the outback town of Gundagai—was of course denied by authorities, and he was instead interred in an unmarked grave at Sydney’s Rookwood Cemetery.

Flash forward 115 years to 1995, when two local Gundagai women, moved by Scott’s century-old burial wishes, led a successful grass-roots campaign to have his body exhumed from Rookwood and transported the 220 miles to North Gundagai Cemetery, where Nesbitt is believed to also lie in an unmarked grave. Scott’s new tomb was given a proper stone marker, and is now a pilgrimage site for fans of both Australian bushranger history and global queer heritage.

New South Wales added Scott and Nesbitt’s graves to its State Heritage Register in March of this year. Minister for Heritage Penny Sharpe said that the listing “reflects the desire to tell the diverse stories that reflect the rich history of NSW” and have “always existed” in the state.

“Captain Moonlite and James Nesbitt were outcasts even among outcasts, who might have lived very different lives in more contemporary times,” she added.

Historian Garry Wotherspoon, who decades ago unearthed Scott’s intimate death-cell letters in a dormant NSW archive, stressed to Australia’s ABC News the importance of highlighting gay relationships from the past to foster recognition that people of diverse sexualities have always existed.

“We’re not a sudden aberration after World War II,” Wotherspoon said. “We’ve always been there.”

Join the GayCities newsletter for weekly updates on the best LGBTQ+ destinations and events—nearby and around the world.

Mark

Mark