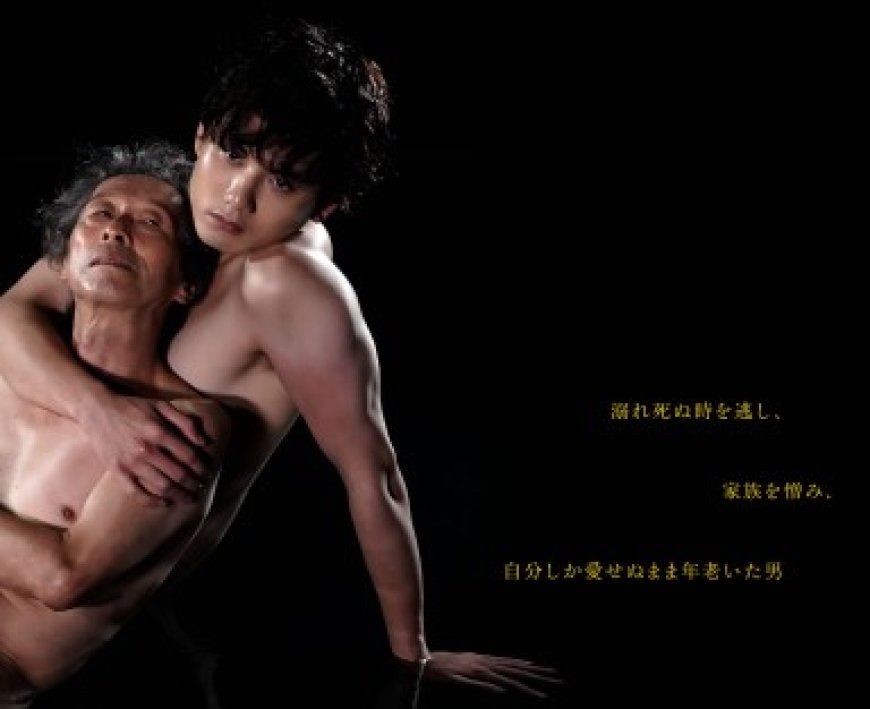

‘Old Narcissus’: At life’s end, a man finally looks beyond himself

Caravaggio’s 16th-century painting “Narcissus,” in which a man bends over and gazes closely into a pool of water reflecting his face back at him, is a touchstone for bi Japanese director Tsuoyoshi Shoji’s latest film. The very first image of “Old Narcissus,” expanded from Shoji’s 2017 short, quotes this artwork, but with a very crucial difference. … Read More

Caravaggio’s 16th-century painting “Narcissus,” in which a man bends over and gazes closely into a pool of water reflecting his face back at him, is a touchstone for bi Japanese director Tsuoyoshi Shoji’s latest film. The very first image of “Old Narcissus,” expanded from Shoji’s 2017 short, quotes this artwork, but with a very crucial difference. Caravaggio depicted a young man who sees himself at the same age. Yamazaki (Taijiro Tamura), a man in his 70s, glances into water and sees the twink he used to be 50 years ago. Periodically, “Old Narcissus” goes back to this scene, which represents Yamazaki’s fantasies and fears. He imagines himself sinking into the pool. Even its more realistic imagery rhymes with this. A close-up of a phone emphasizes the water glistening on its surface. Yamazaki confronts his fears of death at the beach. Escaping from this pool, very late in life, becomes Yamazaki’s mission, even if he doesn’t consciously recognize it.

Yamazaki is a writer of children’s books. He’s diagnosed with prostate cancer, whose treatment may ruin his ability to enjoy sex. He pays Leo (Atomu Mizuishi), a young sex worker, for BDSM sessions. When Leo paddles him, he reaches an epiphany of pain, shown through an animated explosion. For Leo, this is just a job: He’s in a committed relationship with his boyfriend Hayato (Takeshi Terayama). Indeed, they arrange to formalize their partnership to protect each other and adopt a child. (Same-gender marriage still hasn’t been legalized in Japan.) Yamazaki also spends most of his nights at a bar. He joins a group for elderly gay men, where he encounters a former lover whom he resents. He grows to realize that his life has been limited both by homophobia and his own selfishness. Meanwhile, Leo struggles with his own fears about living with Hayato.

Yamazaki is attracted to Leo, not least because he sees his own youth in the escort. One of his reveries, where he and Leo occupy each side of a shot split in half by a baseball bat, makes this plain. (As a teenager, Yamazaki was pressured to play sports as a sign of heterosexual masculinity.) He wants both a lover and alter ego. The extreme age gap between the two men brings out the issue of missing fathers and unborn sons. Yamazaki even considers adopting Leo in order to will him his inheritance. Yamazaki’s generation of gay men was left with no models for a fulfilling life without children. Shoji’s own age lies in between the two.

“Old Narcissus” addresses the generational differences between Leo and Yamazaki sensitively. Without sharing Yamazaki’s revulsion at his own sagging skin, Shoji’s images show the toll of old age. Even without legal marriage, Leo has grown up with far more options as a gay man. But because his father killed himself when he was a child and he had a rocky relationship with his mother, he grew up without parental figures. The fact that he’s a sex worker is not treated as particularly taboo, except when he hides it from his boyfriend’s family. This may be a cultural difference: Being an escort is legal in Japan, and the country’s history of frank films about sex workers’ lives dates back to the 1930s.

At worst, “Old Narcissus” risks treating Leo as a fantasy figure who exists to help Yamazaki. Its ending, where a passage from one of Yamazaki’s books is read over an extended montage, flirts with sentimentality. Alternately, some of Yamazaki’s self-destructive behavior, like paying an unhoused man to paddle him, could lead into misery porn. But the film avoids both paths. The latest entry in Adam Baran’s monthly “Narrow Rooms” screening series, it’s gentler than most of his programming. An upbeat score dictates the film’s mood. Although Shoji’s earlier work isn’t available in the U.S., the poster art and titles like “Woman Omyoji Awakening of Perversion” suggest wild B-movies. (In 2021, he became the first Japanese director to cast a trans actor as a trans character.) “Old Narcissus” is rather sober and earnest. It’s an honest effort at developing drama in these characters’ lives, instead of simply manufacturing it.

“Old Narcissus” | Directed by Tsuoyoshi Shoji | In Japanese with English subtitles | Plays Anthology Film Archives on April 26th, 7:30 PM

Mark

Mark