This revolutionary gay bookstore was held together by “all the wiretaps the FBI ran through it”

Several left-wing groups and a lesbian newspaper used Lambda Rising as a meeting space and the feds took notice. So did the media.

In 1971, Deacon Maccubbin stumbled upon the quaint Oscar Wilde Bookshop on Mercer Street while visiting New York for Pride. Inside, he found no more than a few dozen titles on its racks, but he was amazed to discover a space devoted to gay literature. Upon returning to his hometown of Washington, DC, a revolutionary idea took root in his subconscious, which blossomed over the next few years.

One day, he found himself at a community bookstore in Dupont Circle, gradually emerging as a welcoming neighborhood for the LGBTQ+ community. Around this time, in 1973, homosexuality was declassified as a mental disorder, so understandably, there wasn’t much gay literature readily available beyond condemnation. Still, Maccubbin knew the truth firsthand; the proof was in the pudding – he had seen it with his own eyes.

Pack your bags, we’re going on an adventure

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for the best LGBTQ+ travel guides, stories, and more.

Subscribe to our Newsletter today

“Excuse me, where are your gay books?” he asked the cashier, who pulled down his glasses and stared at him funnily.

“Oh, we don’t carry those books,” the person replied.

Maccubbin resolved that “those books” must be somewhere, so he went to the library. The librarian informed him they had them but couldn’t keep them on the shelves. Either because gay men stole them due to embarrassment or homophobes ripped out their pages or trashed them.

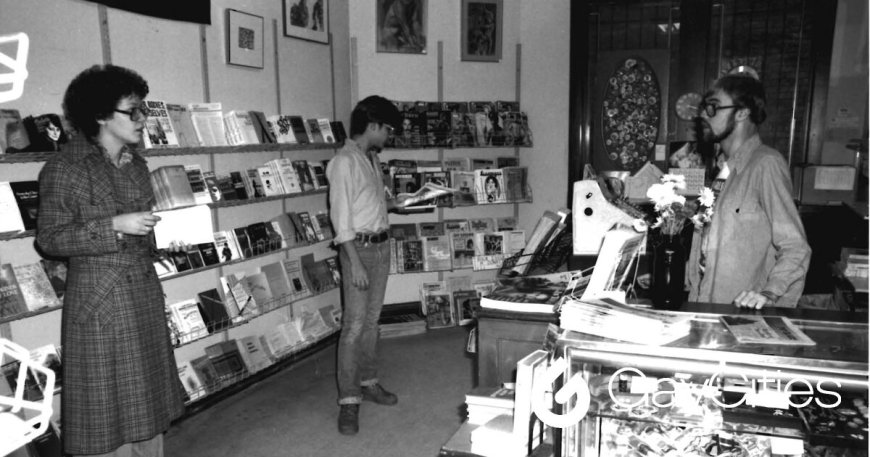

Maccubin tells GayCities he felt a responsibility to fix the situation, which led to Washington DC’s first gay bookstore, Lambda Rising, opening its doors in 1974. He figured the market was out there, but a wall of shame and stigma blocked it. He says the name was derived from an international gay rights organization that used the “lambda” symbol and an underground publication in Chicago called Phoenix Rising.

“I remember a guy coming in two weeks after we opened, and he just did a slow 360-degree turn, looking at everything around him. Then, he let out a huge sigh of relief and said, ‘Home, home at last,'” says Maccubbin.

The newfound gay bookshop owner expected his community to appreciate a haven for their stories and vital information. But he didn’t anticipate the store itself would shelter so much queer joy. Several groups – including left-wing organizations, a lesbian newspaper, and a drug offenders rights committee – started using Lambda Rising as a meeting space.

“We used to joke that the only thing holding the building together was all the wiretaps the FBI ran through it,” says Maccubbin.

Eventually, he relocated to a bigger space on S Street, where an actual mezzanine was upstairs. He offered groups the chance to host formal or social meetings at no charge.

He remembers a gay youth group that met every Saturday afternoon around 2 pm. There were usually between a dozen and two dozen sixteen to twenty-year-olds attending.

“They came to me and my husband and said, ‘We want to let students around the area know this group exists so they know where they can come.’ And they asked for ideas to promote them,” says Maccubbin.

He suggested they put ads in high school newspapers and offered to sponsor them. He sent 70 requests to promote the group primarily in the suburbs, but ultimately, faculty advisors or principals vetoed them except for two school papers that ran it, charging about $35.

“One of the parents somewhere in Northern Virginia complained about the ad to the media,” says Maccubbin.

Of course, the parent was hoping to land Lambda Rising in hot water, but instead, the bookshop and its gay youth group became the city’s hot topic, with publications as notable as the Washington Post and plenty of local TV crews scrambling to run stories on them.

“This little $35 ad somehow generated millions of dollars worth of free publicity,” says Maccubbin. “The youth group grew so much that it eventually evolved into an organization called SMYAL (Supporting and Mentoring Youth Advocates and Leaders).”

Maccubbin says his store was lucky; most of the dangers were limited to broken windows by Neo-Nazis. Other gay bookstores around America and across the sea weren’t so fortunate.

In 1984, Lambda Rising relocated again to a 5,000-square-foot shop on Connecticut Avenue.

That same year, on April 10th, when the clock struck 1 pm in London, two plainclothes men entered Gay’s the Word Bookshop. They identified themselves as customs officers. The hostile men forced all the customers out of the store and locked the doors, accusing the shop of harboring illegally imported or obscene material. They wasted no time in ransacking the bookshelves and confiscating about 100 books, such as Edmund White’s The Joy of Gay Sex, placing them in plastic bags before scurrying away in an unmarked car.

Some staff would have to fight grueling criminal trials for the next few years.

“We considered the dangers, and we always tried to do things safely,” says Maccubbin. “But here’s the bottom line: this is who I am; this is what I’m gonna do.”

The outside world recognized that knowledge wasn’t just an agent of change, but that spaces labeled safe for the LGBTQ+ community could foster the power of connection in all its forms.

The most popularly banned and criticized gay author, Edmund White, tells GayCities that gay bookstores, especially before the apps, were a good place for gay intellectuals to cruise.

“Gays are such heavy drinkers that it was great to have an alternative to gay bars,” says White, who himself was never afraid of a good time. “And they are always good for serendipity—to find titles you’d never heard of, especially by small presses.”

Maccubbin and White’s life experiences with literature are intertwined. The author mentions that the Oscar Wilde Bookshop, along with Gay’s the Word, was the first real literary gay bookstore he ever knew.

Before that, like many gay men, White had to get crafty.

“When I was a gay teen in Cincinnati, Ohio, the main place for cruising was Fountain Square—and there were louche bookstores on the square where you could buy under-the-counter gay ‘physique’ magazines—pictures of boys in posing straps holding a spear,” remembers White fondly.

The significance of bookshops like Lambda Rising is in the countless queer ripples. The eventual waves couldn’t have been made possible if individuals like Maccubbin hadn’t given gay authors like White spaces for their sexualities to thrive and inspire future generations (author included).

In 2010, Lambda Rising closed its doors after 35 years, facing stiff competition from Amazon and online stores. It was part of a series of gay bookstore closures in the 21st century, including the Oscar Wilde Bookshop.

However, a legacy doesn’t end as long as someone else is willing to carry the torch, even if there are gaps in time between. Gay history is never late and always needed. In 2022, Little District Books, a queer-owned bookshop catering to queer literature for all ages, opened on Barracks Row, a thriving commercial district in Washington, DC.

The owner, Patrick Kern, cited Lambda Rising as part of his inspiration.

Mark

Mark