Inside the unlikely reinvention of Mexico’s most infamous prison for gay men

Mexico's General Archive, once a notorious prison, has a gay past that impacts the country's LGBTQ+ community to this day.

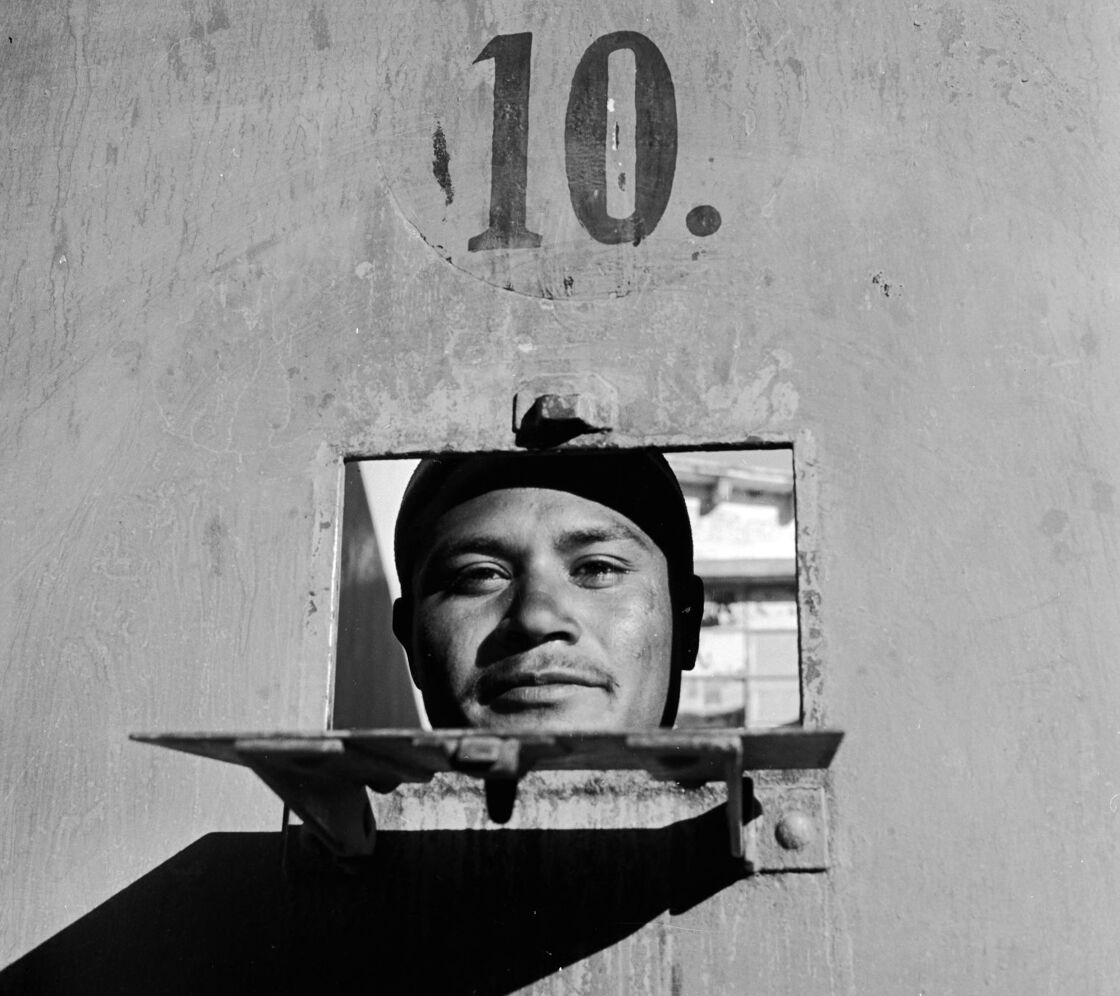

It may look like a fairytale castle, but the Palacio de Lecumberri (“The Black Palace”) in Mexico City has a much darker past. Home to the Archivo General de la Nación (the Nation’s General Archive, AGN), which now holds many of Mexico’s most coveted historical documents, the site operated as a prison with a chilling gay legacy.

Opened in 1900, the facility housed inmate corridors distinguished by letters. Those convicted of “disturbing public order” went to Corridor “J.” In other words, it was the place for queer men who violated the moral standards of Mexico’s conservative society at the time. From this, the slur “jotos” would emerge, derogatory slang for members of the LGBTQ+ community to this day.

Inside the Black Palace

Pack your bags, we’re going on an adventure

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for the best LGBTQ+ travel guides, stories, and more.

Subscribe to our Newsletter today

Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz ordered the construction of Lecumberri Palace, which was intended to be one of the most secure prisons in the country. The structure features panoptic architecture, allowing guards in the tower to observe every part of the building and thus keep the prisoners under complete surveillance. The structure operated as a

Corridors separated inmates by type of crime. For example, the “H” and “I” sections housed tax evaders and those accused of social dissolution and governmental injustices. The great painter and muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, a proponent of left-wing ideology and a contemporary of Diego Rivera, was imprisoned several times for raising his voice against the state.

In his teens, Juan Gabriel (“El Divo de Juárez”), one of Mexico’s greatest musical artists and queer icons, was sentenced to three years at the Black Palace for allegedly stealing a necklace after a private concert, despite lack of evidence. Despite suffering abuse within the prison’s walls, Gabriel’s charm and talent eventually caught the attention of singer Enriqueta Jiménez (also known as La Prieta Linda) and General Andrés Puentes Vargas, who helped negotiate his early release. Jiménez remained a lifelong friend and mentor.

The J-Corridor and origin of “Jotos”

The J-corridor housed men who openly expressed their homosexuality or were discovered engaging in these practices. The 1871 penal code, intentionally vague, left plenty of opportunity to pursue cases against “any action that in the public eye is classified as contrary to modesty.”

Guards and other prisoners subjected J-corridor inmates to various verbal humiliations and physical abuse, popularizing the derogatory term “jotos,” which crossed the thick walls of the Black Palace and found its way into newspaper headlines of the time.

Those held in J-corridor would have their lives changed forever. Flying under the radar was no longer possible, and oftentimes, friends and family would disown them, leaving their professional lives in ruins.

The derogatory phrase “joto” has remained a part of Mexican culture to this day, though some from the LGBTQ+ community are reclaiming it as their own.

The dance of the 41

One particular event links men of Mexico’s high society in the 1900s with the J-corridor – a “scandalous and shameful” incident reported in many newspapers. Police carried out a raid on November 18, 1901, in the Tabacalera neighborhood of Mexico City, targeting a men’s dance. Of the 42 participants, 21 were dressed as men and 21 as women. Most were known as “Pollos” or “Lagartijos,” terms used for those belonging to a high and exclusive social circle.

But only 41 were arrested. Ignacio de la Torre y Mier, son-in-law of Porfirio Diaz, the president of Mexico who had commissioned Palacio de Lecumberri a year earlier, evaded arrest. The Mexican press turned the incident into a scandal, despite the government’s efforts to suppress it. However, it was a juicy topic because the detainees belonged to Mexico’s upper class, representing conservative families with traditional backgrounds.

From prison to national archives

The Black Palace was built for 800 male inmates, but at the height of its use as a prison, it was packed with nearly 3,800 occupants. It also became a setting for creative works, including the 1948 film Nosotros los pobres, director Ismael Rodríguez’s film about a poor carpenter framed for a crime, and José Revueltas’ novel El Apando.

The imposing fortress, with turrets connected by a series of battlements at the top, ceased functioning as a

In addition to its documentary preservation function, the National Archive offers guided tours, a photo library, and a consultation room, enabling visitors to delve deeper into Mexico’s history. But the secrets of the gay lives that changed forever remained buried deep within its walls.

Related

Get your Frida on: Mexico City for first-timers

Visiting Mexico City for the first time? Here’s the ultimate shortlist of how to experience Mexico’s capital like a pro.

Join the GayCities newsletter for weekly updates on the best LGBTQ+ destinations and events—nearby and around the world.

Mark

Mark