Years of nonstop travel have changed my tolerance for risk

I thought these folks were complete idiots, but they were all adults, and I didn’t know any of them well. What could I do?

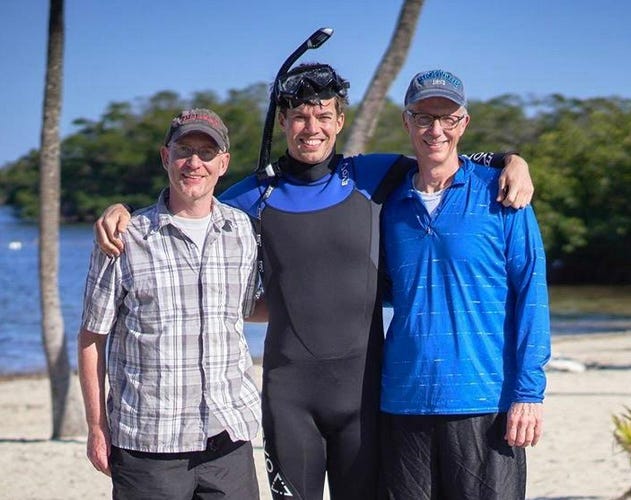

In our first year of nomading, my husband, Michael, and I spent part of the summer in Bansko, Bulgaria — a winter ski town fast becoming a year-round destination for expats and nomads.

On Saturday afternoons, the local ski resort opened the chairlifts to give people access to the alpine hiking trails, and one day, Michael and I joined a group of 15 or so nomads for one of these excursions.

But high on one of those mountain hikes, someone pointed off-trail and said, “You know, I bet if we headed this way, we’d end up back down in town.”

Pack your bags, we’re going on an adventure

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for the best LGBTQ+ travel guides, stories, and more.

Subscribe to our Newsletter today

This is a regular feature about where we currently are in the world: how we ended up there, what it costs, and exactly what we think. Subscribe to our free travel newsletter here.

Some of the group was intrigued, but I looked to where this guy was pointing, and yeah, the town was probably down there somewhere — but there was a pile of massive boulders between here and there.

Plus, it was already late afternoon, and the chairlifts would soon stop running. And did I mention we were high in the mountains?

So I said, “I don’t think that’s such a good idea.”

What I meant was: Are you people out of your freakin’ minds?

“Oh, come on,” someone else said. “It’ll be an adventure.”

But Michael and I looked at each other and rolled our eyes. Before long, the larger gathering split into two groups: most of us returning to the chairlift, and a group of six or so heading off over those boulders.

I thought these folks were complete idiots, but they were all adults, and I didn’t know any of them well. What could I do?

That night, I wondered what became of them, but it wasn’t until the following day that I learned they hadn’t made it back to town until four AM. That pile of boulders had turned out to be something of a sheer cliff, and by the time they realized how dangerous a climb it was, they were already halfway down with no good options.

Two people went to the hospital, one with a twisted ankle and another with symptoms of hypothermia. It was a good thing no one died. No one thought it had been “an adventure.”

Scientists have long known that some folks are drawn to risky activities specifically because they’re risky. The sense of danger releases pleasurable chemicals in their brains.

You know, like serial killers.

And I’ve long known I am not drawn to activities like that. It must be partly because I don’t get these chemicals in my brain, but it’s mostly because I want to go on living, preferably using all my limbs.

Even before I became a nomad, there were people in my life who had a risk tolerance that was some degree of different from mine — and I was always some degree of appalled by the choices they made.

After eight years of nomading, I meet people like that a lot more frequently — crazy idiots like those folks in the mountains in Bulgaria. But I’m not sure it’s because nomads and expats are more prone to taking risks; it might just be because I now meet so many more people.

At Michael’s and my first nomad stop, in Miami, Florida, we hung out with a group that included a “free spirit” named Maggie. Once, Maggie suggested we all hop a ferry for a day trip to the Bahamas the following morning. That sounds like fun, I thought.

But when we checked the ferry schedule, there were still tickets for the ride over, but the boat was sold out for the ride back.

“They’ll probably still let us on,” Maggie said. “But if they don’t, we can just sleep on the beach and come back on the morning ferry.”

Sleep on the beach? I thought, mostly appalled by the idea but also kind of intrigued.

“We can’t do that,” one of our other friends said. “I have to catch a plane back to New York in the morning.”

“Oh, you can make it,” Maggie said, not bothering to ask what time his plane left. “If it were my flight, I’d do it.”

I was pretty sure she was telling the truth. But when Maggie said that, I wasn’t intrigued anymore, just appalled.

The guy with the flight to catch wasn’t buying it either. “Uh, I don’t think so,” he said. So we all decided to rent a car and take a day trip to Key Largo instead.

But on that outing the following day, I kept looking at Maggie and thinking, Is that really how you live your life?

I remembered how we’d also all gone to a midnight moon party on Miami Beach, but Maggie had gone off on her own, hooking up with someone, but not telling anyone until the next morning.

Over the three months I knew her, Maggie also lost a job, abandoned a half-finished volunteer project, and had a, uh, tumultuous love life.

I couldn’t possibly live like that! I thought at the time — and I still think it now, seven years later.

Michael and I have occasionally found ourselves in scary situations, like when our apartment caught on fire — also in Bulgaria.

But even after eight years of travel, nothing that bad has happened to us. And nothing bad has ever happened because we put ourselves in a sketchy situation because we were seeking “adventure” or wanted the rush from taking some risk.

I did occasionally find myself in “danger” in my pre-nomad life in Seattle. But overall, my life feels less risky now—if only because I spend so much less time in cars.

At the same time, my feelings about “risk” have shifted a bit. I might be even more risk-averse than before.

I don’t think it’s (just) a question of age. It’s more because I’ve met more people like Maggie and that group of hikers on that Bulgarian mountain. After you hear or witness many life-disaster stories, you start to examine the timelines, and you often see a point where the person took what I would consider an unnecessary risk.

Not always, of course. Sometimes things just happen. And if travel has taught me anything, it’s that the world is way more unfair than I thought.

Also, none of this means I blame the people who take what I deem to be stupid risks. As judge-y as this essay makes me sound, I don’t wish anyone ill. And I know there are pros and cons to everything. On some level, Maggie’s life is probably more exciting than mine.

Hey, I’m tempting fate simply by saying outright that the older I get, the more I feel like people have at least a fair amount of control over their destinies.

Or maybe all I’m doing here is admitting I’m a control freak. Perhaps I’m too concerned about “risk” to relax and enjoy life’s constantly shifting kaleidoscope.

That isn’t the way it feels; I don’t feel uptight. Most of the time, I feel like I’m leading my best life, having all kinds of fantastic travel adventures, even as I feel like I’m not taking any unnecessary risks.

But what if I’m wrong? What if I am depriving myself of some unexpected joy?

Well, I guess I’ll just have to risk it.

Join the GayCities newsletter for weekly updates on the best LGBTQ+ destinations and events—nearby and around the world.

Mark

Mark